Financing smart cities in China: mechanisms, challenges and the path forward

Wu Jun1,2![]() , Turgel I.D.1

, Turgel I.D.1![]()

1 Ural Federal University, ,

2 Shanghai Hode Information Technology Co., Ltd., ,

Скачать PDF | Загрузок: 41

Статья в журнале

Экономика, предпринимательство и право (РИНЦ, ВАК)

опубликовать статью | оформить подписку

Том 14, Номер 8 (Август 2024)

Эта статья проиндексирована РИНЦ, см. https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=69296598

Аннотация:

The article presents an approach to solving the problem of finding the most rational mechanisms of financing Smart Cities projects. Critically analyzing China\'s experience in the field of digitalization, the authors present new data characterizing the volume and dynamics of financial investments of key actors in these projects. The main results of the study, which determine its novelty, are: characterization of the role of \"Smart Cities\" projects in the system of national planning of socio-economic development of the PRC; assessment of the dynamics and structure of the volume of financing in the context of its main sources (central government, regional governments, private sector). The paper concludes with recommendations for improving the sustainability of financing of these projects. The article will be of interest to researchers, experts, and post-graduate students specializing in digital transformation and urban development.

Ключевые слова: smart cities, socioeconomic impact, municipal management policy, urbanization, China, Russia

JEL-классификация: O23, O38, O53

Introduction

The relevance of the research topic is determined by the following prerequisites. On the one hand, the rapid urbanization that has defined China’s economic rise over the last four decades has necessitated massive infrastructure development in its cities. Today, more than 60% of China’s population resides in urban agglomerations that serve as the engines of economic growth for the country [19] (World Bank, 2022). On the other hand, the speed of China’s urban growth has also given rise to significant challenges around congestion, environmental sustainability, service delivery, public health crises, and more [3, c. 158-160] (Bai, 2014, p. 158-160). With more than 100 cities projected to have over 1 million inhabitants by 2030 [10, с. 7604-7621] (Lu, 2016, p. 7604-7621), the need for a development paradigm shift has become increasingly urgent, especially financing remains a crucial challenge for the advancement and sustainability of China's smart city ambitions. Thus, it can be said that there is a serious problem associated with finding the most rational and effective mechanisms for financing smart city projects. Modern researchers are trying to find approaches to its solution. Thus, considerable attention is paid to issues related to the justification of the role of smart city projects in economic development; substantiation of the essence of the "Smart City" phenomenon [2, с. 234-245] (Ahvenniemi, Huovila, Pinto-Seppä, & Airaksinen, 2017, p. 234-245); [8, c. 10-27] (Goerzen, 2023, p. 10-27); [9, с. 33-48] (Wu, Turgel, 2024, p. 33-48). Chen C. examines the processes of the origin and evolution of smart cities in China [4, с. 966–974] (Chen, 2018, p. 966–974). Todaro focuses on studying the most striking cases of digitalization projects in Chinese cities [18, с. 295–554] (Todaro, 2024, p. 295–554). Xu W. and, Xu J. They explore certain aspects of the use of public-private partnerships in smart city projects [24] (Xu and Xu, 2024). However, there is a shortage of integrated approaches that take into account the diversity of actors involved in the development of smart cities and the special role of the country's central government in initiating these projects.

The above-mentioned circumstances determined the aim and methodology of the study. The aim of this research is to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the financing mechanisms that have enabled China's smart city initiatives over the past decade. The basis of the author's methodology is a system-structural analysis. The system-structural approach is an approach to considering an object as a system, as a result of the interaction of its elements, as well as its understanding as part of a larger system. To solve private research problems, the method of studying normative documents, the method of statistical analysis, and the graphical method were used.

In the course of the study, the hypothesis was formulated and confirmed that the successful solution of the problems of financing smart city projects requires clear goal-setting and integration of the efforts of all key actors: the central government, subnational governments and the private sector.

Main part

Smart Cities in Chinese Strategic Thought

China formally placed the “smart city” within its national development strategy through two key policy roadmaps: the 12th Five Year Plan (2011-2015), which governs the country’s economic and social development targets; and the National New-Type Urbanization Plan (2014-2020), which lays out urban modernization goals. Enabled by growing technological capacity, political commitment at the highest levels, and a recognition that the current urban paradigm was untenable, these plans envisaged smart cities as a catalytic intervention that could steer Chinese cities towards greater efficiency and sustainability while cementing the country’s reputation as an innovation leader [4, с. 966–974] (Chen, 2018, p. 966–974).

The first wave of smart city pilots from 2010-2013 embodied China’s techno-optimistic vision. Top-down in their approach, many initiatives focused disproportionately on advanced ICT infrastructure and intelligent operations centers without adequately assessing localized needs [27, 28] (Zhang, 2023, c. 1-15, Zen Soo, 2018, p. 1-15). However, evaluations from this period highlighted that technology alone could not transform urban environments holistically without also addressing underlying governance, social and economic structures in Chinese cities [11, c. 392-408] Meijer, 2016, p. 392-408). This led to an evolution in strategic thinking around smart cities, with later five-year plans, policies, and demonstration zone criteria incorporating greater emphasis on public services, entrepreneurship, and sustainability beyond purely technical metrics [8, c. 10-27] (Goerzen, 2023, p. 10-27).

The 13th Five Year Plan approved in 2016 marked a particularly noteworthy advancement in how smart cities feature within China’s national development roadmap. It outlined an ambitious vision spanning intelligent transportation, connected energy systems, technological innovation ecosystems, and e-governance platforms [21] (Xinhua, 2016). The State Council set minimum threshold targets related to broadband penetration, networked sensors, integrated operations centers, and municipal data utilization that all smart city pilots would need to fulfill. In turn, successful demonstration zones would receive favorable regulatory conditions and preferential financial incentives to catalyze replication [29, c. 25-53] (Zou, 2023, p. 25-53). This expansion of China’s smart city ambitions reflected a growing confidence in its own technological capacities, increasing private sector involvement beyond state-owned technology enterprises, and recognition of smart cities’ strategic value on multiple fronts – sustaining economic growth as the working-age population declines; upgrading traditional infrastructure to boost productivity; leveraging technological innovation for global influence; enhancing public service delivery and social stability; and accelerating low-carbon, sustainable urbanization [28, c. 1-15] (Zhang, 2023, p. 1-15).

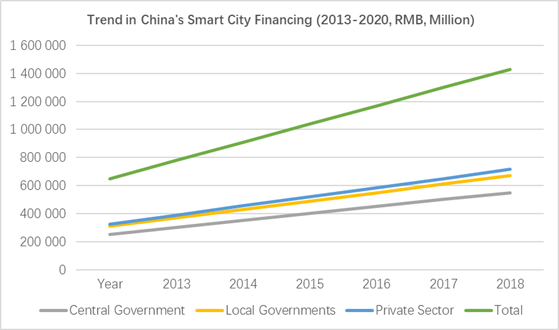

With the 13th Five Year Plan period ending in 2020 giving way to the 14th Five Year Plan (2021-2025), smart cities remain firmly ingrained within China’s national development strategy. The most recent roadmap calls for 80% urbanization across China by 2035, necessitating further expansion of intelligent transportation systems, smart grids, pollution reduction technologies and e-governance platforms in its cities [23] (Xinhua, 2021). Moreover, policies like the “New Infrastructure” plan that catalyzed post-COVID recovery through investments in 5G, ultra-high voltage electricity, intercity transportation, big data centers, artificial intelligence, and IoT also clearly intersect with smart city advancement [22] (Xinhua, 2020). As China contends with complex demographic, environmental and economic challenges in the coming decade, technologies and governance innovations pioneered under the smart cities paradigm will likely take on heightened strategic importance [28, c. 1-15] (Zhang, 2023, p. 1-15). With hundreds of pilots and demonstration zones maturing, the models that prove most replicable and scalable stand to shape city building long after immediate Five Year Plan periods pass. However, for any smart cities to actually fulfill that transformative potential, sustainable financing remains crucial and yet unresolved. The figure below shows the trend of financing smart cities projects in China from 2013 to 2020:

Figure 1:Trend in China’s Smart City Financing, 2013-2020 [29, c.25-53] (Zou, 2023, p. 25-53)

For a more detailed observation on the changes of China's vision, financial tools, and aims for smart cities across the 12th, 13th, and 14th Five Year Plans, please see the table 1:

|

|

Vision

|

Financial

Tools

|

Quantitative

Targets

|

Aims

|

|

12th

Five Year Plan (2011-2015)

|

Laying

foundation for smart cities through pilots focused on ICT infrastructure and

intelligent operations centers

|

National

New-Type Urbanization Plan funds (RMB 2 trillion total)

Initial Ministry of Housing grants |

500

pilot smart city projects launched

|

Test

smart technologies Build digital governance foundations Establish technical

standards Economic restructuring Foster techno-innovation ecosystems Enhance

public services Promote sustainable urbanization Showcase global leadership

|

|

13th

Five Year Plan (2016-2020)

|

Comprehensive

smart city ecosystem spanning intelligent transport, energy, urban services,

public safety, and innovation hubs

|

· National Innovation-Driven Development

Strategy funds (RMB 70 billion+)

· Expanded Ministry grants/awards · Municipal bonds for projects · Public-private partnerships · New Infrastructure investment plan |

· 80% cities meet minimum thresholds

for:

· Broadband coverage · IoT sensor deployment · Integrated operations centers · Municipal data utilization |

Social

governance efficiency Competitive economic clusters Resilient urban

infrastructure

|

|

14th

Five Year Plan (2021-2025)

|

Widespread

replication and scaling of proven smart city models, with emphasis on new

infrastructure integration (5G, AI, big data)

|

· MOHURD Public-Private Partnership Fund

(RMB 10 billion)

· Local government special bonds · Policy bank loans |

80%

urbanization rate by 2035 Full 5G coverage in cities "AI +" applied

across urban domains New infrastructure foundation built

|

High-quality

urbanization Smart industry integration Technological self-reliance Carbon

neutrality advancement

|

Financing from Central Government

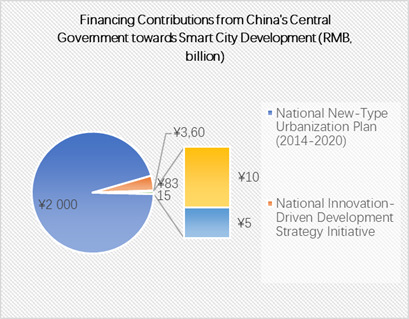

The central government in China has mobilized substantial financial resources to catalyze smart city development across the country. The figure 2 summarizes the major funding instruments and their contributions:

Figure 2: Financing Contributions from China's Central Government towards Smart City Projects, 2011-2020 [12] (MOHURD, 2021).

While a substantial sum was earmarked by the central ministries, only an estimated 25% was directly utilized for smart city pilots and demonstration zones due to bottlenecks like local government capacity and underdeveloped projects. Recognizing that financing represented perhaps the most significant bottleneck for widespread smart city diffusion, China’s central government introduced several key instruments and incentives to catalyze development. Efforts focused both on increasing available funds through planning budgets and innovation funds for technological advancement relevant to smart cities, as well as incentivizing local governments to launch self-sustaining initiatives through competitive subsidies. Among these documents, the Five Year Plans are the overarching national development blueprints that set the broad economic and social priorities for China over each five-year period. They are formulated by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and approved by the National People's Congress. The National New-Type Urbanization Plan (2014-2020) and the National Innovation-Driven Development Strategy were semi-independent policy documents, but derived their mandates and funding from directives laid out in the 12th and 13th Five Year Plans respectively. Specifically, the 12th Five Year Plan (2011-2015) called for "accelerating urbanization" and promoting strategic emerging industries like new energy, biotechnology and next-generation IT. This provided the basis for The National New-Type Urbanization Plan, which allocated RMB 2 trillion for urban infrastructure and tech upgrades, some of which went towards initial smart city pilots.

The 13th Five Year Plan (2016-2020) went further by explicitly highlighting "smart cities" as a national priority, aiming to make China a global leader in this domain. It dedicated a full section to articulating smart city targets. This enabled The National Innovation-Driven Development Strategy, which provisioned RMB 70 billion+ for venture funds, research parks and pilot zones focused on smart city technologies and innovative urban governance models. In summary, the Five Year Plans set the high-level vision, priorities and policy direction for China's economic and social development over each five-year period. More specific national plans/strategies like those for urbanization and innovation get crafted to implement the Five Year Plan mandates through concrete policy instruments, funding pools, targets and initiatives.

The system flows in a top-down hierarchy, with the Five Year Plans as the supreme guiding documents. All ministries, local governments and major state initiatives must then align their policies and actions to the current Five Year Plan objectives.

National New-Type Urbanization Plan: As outlined earlier, this RMB 2 trillion ($314 billion) infrastructure and technological upgrade fund for Chinese cities represented the largest central government financing source explicitly intended to propel smart city pilots [8, c. 10-27] (Goerzen, 2023, p. 10-27). However, only about 10% ultimately went towards intelligent transportation, connected energy systems, e-governance platforms, emergency response centers and other smart urban projects [29, c. 25-53] (Zou, 2023, p. 25-53). Experts suggest bureaucratic inertia around traditionally physical infrastructure along with limited local government absorptive capacity led to underutilization of the NUTP fund for smart city development [28, c. 1-15] (Zhang, 2023, p. 1-15).

National Innovation-Driven Development Strategy: This broader national strategy launched in 2016 focuses on technological upgrading, emerging industries and homegrown innovation across multiple domains from biotechnology to advanced manufacturing. Within it, the central government allocated RMB 13 billion ($2 billion) in venture capital towards smart city technological innovation like intelligent sensors, municipal data platforms, decision-support systems for city administrators and digital citizen engagement models [8, c. 10-27] (Goerzen, 2023, p. 10-27). An additional RMB 70 billion ($11 billion) financed pilot demonstration zones, tech startups and research parks relevant to urban technological advancement [26, c. 1-14] (Yuan, 2019, p. 1-14).

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD) Subsidies: Beginning in 2015, MOHURD instituted competitive grants worth RMB 500 million annually to catalyze exemplary smart city pilots that could then be scaled up nationwide [26, c. 1-14] (Yuan, 2019, p. 1-14). By 2020, the ministry awarded RMB 3.6 billion to over 300 pilots across multiple categories like comprehensive smart cities, intelligent transportation, connected energy systems and smart villages integrated with urban clusters [12] (MOHURD, 2021). Successful demonstration zones received bonus funds and supportive regulatory conditions to accelerate replication.

MOHURD Partnership Fund: In late 2021, MOHURD launched this RMB 10 billion fund explicitly focused on attracting greater private investment into smart city development through public-private partnerships [5] (China Daily, 2021). By de-risking initial financing needs for technological integration companies along with operations, maintenance and training partners, the fund aims to incentivize commercially viable smart cities. Early funds have focused especially on industrial internet and integrated smart energy pilots.

National Key R&D Programs: China’s Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) oversees several National Key R&D Programs centered on scientific innovations with strategic importance, many of which relate closely to smart city advancement. From advanced sensors and IoT connectivity to big data platforms, MOST has funded over 500 smart city related projects worth RMB 5 billion under initiatives like the National Key Technology R&D Program, National Key Research Program, and National Engineering Lab Development Program [25, c. 1-18] (Yin, 2015, p. 1-18).

In sum, China’s central government has mobilized over RMB 2.4 trillion (~$380 billion) towards smart city development when including urbanization funds, strategic emerging industry support, MOHURD subsidies, specific innovation research programs and more. However, only about 25% got utilized directly for smart city pilots and demonstration zones [29, c. 25-53] (Zou, 2023, p. 25-53). As later sections will discuss, bottlenecks like local government capacity, incentive misalignments and private sector hesitation have all contributed towards this significant underutilization of available financing from national sources.

Financing from Local Governments

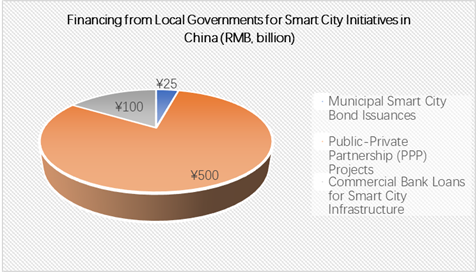

Receiving both policy mandates and financial resources from the central government, local municipal authorities across China's provinces and cities operationalized smart city development using several key mechanisms, as shown in Figure 3:

Figure3: Financing from Local Governments for Smart City Initiatives in China, 2013-2020 [26, c. 1-14] (Yuan, 2019, p. 1-14)

However, there existed a significant disparity in financing capacity between large megacities able to issue bonds versus smaller municipalities that struggled to fund smart city projects. Most of the debt and PPP funds were concentrated in major urban centers. Even as China’s central ministries and national agencies attempted to catalyze smart city initiatives through monetary and regulatory incentives, ultimate implementation depended on the commitment and capacity of local governments in provinces, cities and counties across China. Scholars have highlighted that because success depended heavily on local contextual knowledge and cooperation between multiple administrative stakeholders with sometimes competing interests, smart city development instituted primarily through top-down, centralized avenues achieved limited traction [2, 28] (Ahvenniemi, 2017, p. 234-245, Zhang, 2023, p. 1-15). Without ‘ground truthing’ pilots to fit localized end user requirements and building community buy-in, technological integration alone failed to constitute transformative smart cities.

Recognizing this reality, China’s central government pushed greater authority and autonomy to municipal governments for launching initiatives attuned to unique demographic profiles, economic bases, environmental challenges and governance dynamics in their cities [8, c. 10-27] (Goerzen, 2023, p. 10-27). Mechanisms like the National Innovation City program launched in 2012 provided select municipalities special regulatory privileges to catalyze clustered innovation ecosystems, attract private investment in locally motivated smart city technologies, and institute governance reforms needed to derive maximum value from advanced infrastructure [13] (MOST, 2022). Many such innovation cities like Hangzhou, Wuhan and Chengdu have now emerged as leaders in intelligent transportation systems, safe cities platforms, smart energy pilots and health data analytics applicable to cities nationwide [26, c. 1-14] (Yuan, 2019, p. 1-14).

With greater autonomy, however, came greater responsibility to self-finance smart city development. Especially following initial pilots from 2010-2015, local governments bore the onus of sustaining promising demonstration zones, evolving technologies to suit expanding needs, and integrating operational maintenance into municipal budgets [29, c. 25-53] (Zou, 2023, p. 25-53). This represented a significant challenge since fiscal conditions varied drastically across China’s urban landscape. Mega cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen with strong revenue streams from land sales, local taxes and fees could mobilize substantial municipal bonds towards capital investment in visible smart city infrastructure [26, c. 1-14] (Yuan, 2019, p. 1-14). Using mechanisms like Special Purpose Vehicles, they also attracted domestic and foreign corporations to participate in commercially viable initiatives through public-private partnerships. However, smaller provincial cities struggled to fund even rudimentary pilots beyond initial innovation grants and lacked the creditworthiness to take on significant debt burdens for integrated smart city development [8, c. 10-27] (Goerzen, 2023, p. 10-27).

Since 2013, local governments across China have issued nearly RMB 25 billion worth of Municipal Special Bonds explicitly for smart transportation, safe cities platforms, integrated operations centers, environmental monitoring infrastructure and other smart urban domains [14] (National Bureau of Statistics, 2022). Major cities like Shanghai, Shenzhen, Guangzhou and Suzhou contributed disproportionately to smart city bonds while counties and smaller municipalities lacking fiscal space could not tap this avenue. Local governments also directly financed over 500 smart city public-private partnership (PPP) projects worth RMB 500 billion, though over half the investment centered in Tier 1 megacities [26, c. 1-14] (Yuan, 2019, p. 1-14). And at least RMB 100 billion in commercial bank loans backed by municipal collateral also flowed towards convention centers, cloud computing hubs and integrated emergency response systems embedded within smart cities [8, c. 10-27] (Goerzen, 2023, p. 10-27).

In all, local governments marshaled around 35% of the estimated RMB 3 trillion total financing for smart cities between 2013-2020 using tools spanning bonded debt, PPPs, commercial loans and more [5] (China Daily, 2021). However, persistent inequality in fiscal and financial conditions across China’s vast urban landscape continued to impede scalable smart city development.

Private Sector Financing

Despite consistent policy emphasis on public-private partnership models, private investment accounted for only around 15% of total smart city financing in China from 2013-2020. Key private participation is summarized in table 2:

|

Entity

|

Nature

of Involvement

|

Estimated

Investment

|

|

Tech

Giants (Alibaba, Tencent, Huawei etc.)

|

Pilot

technology testing, some operations

|

RMB

50 billion

|

|

Global

Multinationals (Cisco, IBM, Siemens etc.)

|

Technology

provided for demonstrations

|

RMB

25 billion

|

|

Real

Estate Developers

|

Integrated

smart townships/communities

|

RMB

25 billion

|

|

Other

Private Enterprises

|

Niche

products/services for city operations

|

RMB

50 billion

|

|

Total

|

|

Around

RMB 150 billion

|

The lack of proven revenue models, governance frameworks and risk appetites deterred greater enthusiasm from private players beyond bespoke projects in partnership with local governments. Beyond direct public financing through national and local government channels, private capital has also contributed towards China’s smart city initiatives. However, actual private investment remains far below potential and government targets. By most expert estimates, only around 15% of total smart city investment in China received non-state financing even as policies consistently emphasize public-private partnership models [29, c. 25-53] (Zou, 2023, p. 25-53). Both domestic and global corporate investors continue harboring reservations about risk-return profiles, bankability of projects, capacity of government partners and maturity of technological solutions [2, c. 234-245] (Ahvenniemi, 2017, p. 234-245). Nonetheless, some high-visibility initiatives resulted:

Corporate Technology Partners: Chinese infotech giants like Alibaba, Tencent, Huawei and Baidu directly financed numerous smart city pilots across the country both for reputational gains and to test commercialized applications of emerging innovations from IoT to cloud computing to big data analytics. Alibaba’s City Brain optimization platform got adopted in Hangzhou, Macau and Malaysia while Tencent funded safe city and related enterprise cloud offerings in police video analytics. For these private corporations, their own technologies constituted the primary motivation and competitive differentiation rather than commercially sustainable smart city operations.

Overseas Technology Multinationals: Siemens, Cisco, Microsoft, IBM, Qualcomm and Intel have participated extensively in demonstrations abroad that got replicated in China like intelligent transportation testbeds, air quality monitoring networks and smart energy microgrid integrations. While unwilling to directly lead procurement and operationalization, their technologies helped pilot globally proven solutions even if scaled implementations remain lacking.

Integrated Private Infrastructure: Privately financed showcase developments like the Sino-Singapore Tianjin Ecocity, Alibaba’s Olympic Tower smart office complex in Hangzhou and the Vanke Future City Community project in Shenzhen highlight cutting-edge smart city integration but remain isolated instances dwarfed by the broader urban landscape. Most private real estate developers continue finding comprehensive smart cities financially unviable.

In all, despite high expectations, China’s policies have thus far failed to stimulate significant private sector enthusiasm and investment commensurate with the scale and proliferation of its nationwide smart city initiatives.

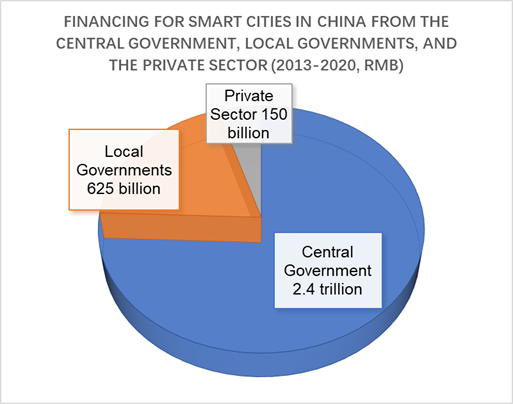

Investment Summary

Here in figure 4 is a visualization demonstrating the ratio/proportion of financing for smart cities in China from the central government, local governments, and the private sector:

Figure 4: Proportion of Smart City Financing in China by Source, 2013-2020 [29, c. 25-53] (Zou, 2023, p. 25-53)

This pie chart clearly shows that the central government provided the lion's share of financing at 75% of the total RMB 3.175 trillion mobilized for smart city projects between 2013-2020. Local governments contributed around 19.5%, while private sector accounted for only 4.7%. The predominant financing role is played by China's central government ministries and agencies in catalyzing smart city development nationwide. Local authorities and private players, while involved, contributed far lower shares of the total investment.

Between the tabular and graphical representations, it is evident that smart city financing in China from 2013-2020 was overwhelmingly driven by funding from the central government level. Local governments and private sector participation remained comparatively modest during this initial phase of smart city deployments across the country.

The findings above highlight significant challenges that threaten the long-term sustainability and scalability of smart city initiatives across China despite over a decade of policy prioritization and substantial financing totaling approximately RMB 3 trillion ($470 billion). While this aggregate investment has enabled an initial foundation with over 500 pilot projects and technological familiarity in cities like Shenzhen, Shanghai, and Guangzhou [5] (China Daily, 2021), several barriers now risk impeding smart cities from genuinely transforming urban life nationwide.

One of the central issues identified relates to the inability thus far to establish sustainable long-term funding sources for smart city operations. Many of the capital expenditures in major cities were financed through land sales revenues, temporary central government grants, or one-off municipal bond issuances [8, 29] (Goerzen, 2023, p. 10-27, Zou, 2023, p. 25-53). However, little emphasis was placed on devising reliable streams of own-source revenue to sustain smart city implementations and services beyond initial pilots.

The research also uncovered the challenge of rising debt burdens from extensive municipal bond issuances and bank loans used to finance smart city infrastructure development. Most initial pilots focused primarily on capital projects without instituting requisite governance reforms or efficiency improvements [28, c. 1-15] (Zhang, 2023, p. 1-15). Consequently, city budgets continue bearing high staffing and operational expenses for previously manual processes that have not been intelligently automated. This scenario of escalating expenditures amid a dearth of revenue-generating services significantly strains municipal finances, making debt repayment for prior smart city investments increasingly untenable [28, c. 1-15] (Zhang, 2023, p. 1-15).

While Chinese policy has consistently promoted public-private partnership (PPP) models for smart cities, the findings indicate continued private sector hesitation beyond isolated pilots and showcase projects. For risk-averse domestic technology enterprises, opportunities to simply test solutions provide insufficient incentive for pursuing comprehensive urban integration plays where profitability remains uncertain [27, c. 1-15] (Zen Soo, 2018, p. 1-15). Global multinationals have participated in smart city demonstrations by providing hardware and software, but complex bureaucratic stakeholders coupled with ambiguities around data governance frameworks limit their willingness to scale operations considerably.

Another impediment identified relates to bureaucratic frictions and institutional misalignments that fragment smart city financing and implementation efforts. With different departments like infrastructure agencies, technology bureaus, service providers and urban planners all independently pursuing siloed priorities like intelligent transportation, public safety or environmental monitoring - funding allocations become disjointed rather than facilitating cohesive, integrated smart city development [28, c. 1-15] (Zhang, 2023, p. 1-15). This lack of coordination across municipal entities exacerbates challenges in attracting sustained private participation for holistic, scalable projects.

Finally, the findings highlight how limited legal and regulatory frameworks surrounding emerging smart city technologies pose risks that further deter greater private investment. Unclear protocols around data ownership, privacy preservation, algorithmic accountability and permissible civic monitoring constrain corporate willingness to deploy solutions with far-reaching public impacts in the absence of formal governance guardrails [29, c. 25-53] (Zou, 2023, p. 25-53). Despite enthusiasm for pilots thus far, businesses inevitably remain cautious about overarching smart city proliferation until robust regulatory practices match technological maturity.

Conclusion (сокращено)

This comprehensive research endeavored to analyze the critical financing mechanisms underpinning China's smart city development over the past decade. In examining the strategic policy context, it highlighted how smart cities became deeply ingrained within China's national development plans and urbanization strategies from the 12th Five Year Plan onwards. Scrutinizing funding sources revealed that the central government deployed a multitude of instruments like the National New-Type Urbanization Plan, innovation funds, R&D programs and competitive subsidies totaling over RMB 2.4 trillion to catalyze smart city pilots and demonstration zones nationwide.

At the operational level, provincial and municipal governments mobilized an additional RMB 625 billion cumulatively through municipal bonds, public-private partnerships, and commercial bank loans to finance localized smart city infrastructure and implementations. However, this local financing exhibited stark disparities based on the fiscal strengths of different cities. The private sector, despite consistent policy directives favoring participation, contributed a modest RMB 150 billion - primarily from technology giants testing products rather than pursuing comprehensive urban integration plays.

However, bottlenecks around sustainable funding models, debt repayment constraints, lack of profitability for private players and bureaucratic misalignments now threaten continued advancement. To resolve such prevailing challenges, the research proposed exploring innovative public financing tools like land value capture levies, citizen investment platforms and municipal data trusts. It also recommended policy measures like regulated data governance frameworks, technical interoperability standards and coordinated multi-city implementation to enhance the overall ecosystem for smart city proliferation.

Cumulatively, this exhaustive analysis elucidated how robust top-down funding from China's central leadership combined with operational financing from local governments enabled the country's commendable smart city strides over the last decade. With appropriate models catalyzing sustainable investment, China's smart city drive can fulfill its transformative promise for economic restructuring, technological innovation, livability enhancement and environmental resilience in the years ahead.

Источники:

2. Ahvenniemi H., Huovila A., Pinto-Seppä I., Airaksinen M. What are the differences between sustainable and smart cities? // Cities. – 2017. – № 60. – p. 234-245.

3. Bai X., Shi P., Liu Y. Realizing China's urban dream // Nature. – 2014. – № 509. – p. 158–160. – doi: 10.1038/509158a.

4. Liao R., Chen L. An evolutionary note on smart city development in China // Frontiers of Infomation Technology & Eclectronic Engineering. – 2022. – № 23. – p. 966–974. – doi: 10.1631/FITEE.2100407.

5. Chernova O. A. et al. Role of digitalization of logistics outsourcing in sustainable development of automotive industry in China // R-Economy. – 2023. – № 2. – p. 123-139. – doi: 10.15826/recon.2023.9.2.008.

6. China Daily China’s smart city market set to top $320 b mark by 2026: Report. China Daily Asia. 29 October 2021. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202110/29/WS617c2346a310cdd39bc74174.html (дата обращения: 5.05.2024).

7. Choudhury S.R. The Dark Side of China’s Smart Cities. The Diplomat. 3 August, 2018. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://thediplomat.com/2018/08/the-dark-side-of-chinas-smart-cities/ (дата обращения: 17.05.2024).

8. Goerzen A., Smussen C.G., Nielsen B.B. Global cities, the liability of foreignness, and theory on place and space in international business // Journal of International Business Studies. – 2023. – № 55(1). – doi: 10.1057/s41267-023-00672-5.

9. Jun Wu, Тургель И.Д. Smart city, digital economy and government's involvement // Информатизация в цифровой экономике. – 2024. – № 1. – p. 33-48. – doi: 10.18334/ide.5.1.120339.

10. Lu D., Tian Y., Liu V. Y., Zhang Y. The performance of the smart cities in China - A comparative study by means of self-organizing maps and social networks analysis // Sustainability. – 2015. – № 7(6). – p. 7604-7621. – doi: 10.3390/su7067604.

11. Meijer A., Bolívar M. P. R. Governing the smart city: a review of the literature on smart urban governance // International Review of Administrative Sciences. – 2016. – № 82(2). – p. 392-408. – doi: 10.1177/0020852314564308.

12. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD) Overview of National Smart City Pilots. 5 January 2021. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/wjfb/202101/t20210105_251544.html (дата обращения: 01.05.2024).

13. Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) National Innovation City. 2022. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.most.gov.cn/eng/programmes1/200610/t20061030_36224.htm (дата обращения: 24.07.2024).

14. National Bureau of Statistics Local Government Debt Audit Results. 2022. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/ (дата обращения: 28.04.2024).

15. National People\'s Congress The12th Five Year Plan, 2011. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://english.www.gov.cn/12thFiveYearPlan/ (дата обращения: 26.04.2024).

16. National People\'s Congress The 13th Five Year Plan, 2016. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/policies/202105/P020210527785800103339.pdf (дата обращения: 26.04.2024).

17. National People\'s Congress The 14th Five Year Plan, 2021. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/2021fs06-national-14th-five-year-plan-20210610-e.pdf (дата обращения: 26.04.2024).

18. Todaro, D. Public Sector AI Applications in Shanghai. / In: The Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Public Sector in Shanghai: Ambition, Capacity and Reality. - Palgrave Macmillan Singapore, 2024. – 295-554 p.

19. World Bank Urban Development Overview. World Bank, 2022. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment (дата обращения: 15.04.2024).

20. Wu J., Lin K., Sun J. The impact of smart city construction on urban energy efficiency: evidence from China // Environment, Development and Sustainability. – 2024. – doi: 10.1007/s10668-024-04916-8.

21. Xinhua China names 500 model smart cities after 5 years of exploring. Xinhua. 29 December 2016. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-12/29/c_135935437.htm (дата обращения: 23.04.2024).

22. Xinhua China rolls out plan for new infrastruction list with 5G, AI leading the way. Xinhua. 23 April 2020. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-04/23/c_138999670.htm (дата обращения: 26.04.2024).

23. Xinhua China outlines 14th Five-Year Plan blueprint, eyes 2035 vision. Xinhua. 12 March 2021. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://english.news.cn/20210312/c9c194c1c5194079aee97f4da97b44c0/c.html (дата обращения: 26.04.2024).

24. Xu W., Xu J. // Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments. – 2024. – p. 103699. – url: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221313882400095X.

25. Yin C., Xiong Z., Chen H., Wang J., Cooper D., David B. A literature survey on smart cities // Science China Information Sciences. – 2015. – № 58(10). – p. 1-18.

26. Yuan L. Three problems that impede the development of smart cities in China. DutchCham White Paper, 2019. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: Retrieved from: https://dutchchamber.cn/sites/default/files/white_paper_-_smart_cities.pdf (дата обращения: 01.05.2024).

27. Zen Soo Z. China’s quest for smart cities faces challenges over growth, coordination. South China Morning Post. 14 September 2018. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.scmp.com/tech/enterprises/article/2164670/chinas-quest-smart-cities-faces-challenges-over-growth (дата обращения: 20.04.2024).

28. Zhang Youzhi, Liu Yinke, Zhao Jing, Wang Jingyi. Smart city construction and urban green development: empirical evidence from China // Scientific Reports. – 2023. – № 13(1). – p. 1-17. – doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-44061-2.

29. Zou X. Eco-City Development in China: International Perspective and Comparaison. / _Urban Sustainable Development in East Asia. Urban Sustainability. - Springer, Singapore, 2023. – 25–53 p.

Страница обновлена: 13.01.2026 в 09:30:28

Download PDF | Downloads: 41

Финансирование умных городов в Китае: механизмы, проблемы и пути продвижения вперед

U T., Turgel I.D.Journal paper

Journal of Economics, Entrepreneurship and Law

Volume 14, Number 8 (August 2024)

Abstract:

В статье представлен подход к решению проблемы поиска наиболее рациональных механизмов финансирования проектов «Умных городов». Критически анализируя опыт Китайской Народной Республики в сфере цифровизации, авторы вводят в научный оборот новые данные, характеризующие объемы и динамику финансовых вложений ключевых акторов данных проектов. Наиболее важными результатами исследования, определяющими его новизну, являются: характеристика роль проектов «Умных городов» в системе общенационального планирования социально-экономического развития КНР; оценка динамики и структуры объема финансирования в разрезе его ключевых источников (центральное правительство, региональные органы управления, частный сектор). В заключении сформулированы рекомендации для повышения устойчивости финансирования данных проектов. Статья будет интересна исследователям, экспертам, аспирантам, специализирующимся в сфере цифровой трансформации и городского развития.

Keywords: умный город, социально-экономическое воздействие, политика в сфере муниципального управления, урбанизация, Китай, Россия

JEL-classification: O23, O38, O53

References:

Abowitz D.A., Toole T.M. (2010). Mixed method research: fundamental issues of design, validity, and reliability in construction research Journal of Construction Engineering and Management. (136(1)). 108-116. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000026.

Ahvenniemi H., Huovila A., Pinto-Seppä I., Airaksinen M. (2017). What are the differences between sustainable and smart cities? Cities. (60). 234-245.

Bai X., Shi P., Liu Y. (2014). Realizing China's urban dream Nature. (509). 158–160. doi: 10.1038/509158a.

Chernova O. A. et al. (2023). Role of digitalization of logistics outsourcing in sustainable development of automotive industry in China R-Economy. 9 (2). 123-139. doi: 10.15826/recon.2023.9.2.008.

China Daily China’s smart city market set to top $320 b mark by 2026: ReportChina Daily Asia. 29 October 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2024, from https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202110/29/WS617c2346a310cdd39bc74174.html

Choudhury S.R. The Dark Side of China’s Smart CitiesThe Diplomat. 3 August, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2024, from https://thediplomat.com/2018/08/the-dark-side-of-chinas-smart-cities/

Goerzen A., Smussen C.G., Nielsen B.B. (2023). Global cities, the liability of foreignness, and theory on place and space in international business Journal of International Business Studies. (55(1)). doi: 10.1057/s41267-023-00672-5.

Jun Wu, Turgel I.D. (2024). Smart city, digital economy and government's involvement Informatizatsiya v tsifrovoy ekonomike. 5 (1). 33-48. doi: 10.18334/ide.5.1.120339.

Liao R., Chen L. (2022). An evolutionary note on smart city development in China Frontiers of Infomation Technology & Eclectronic Engineering. (23). 966–974. doi: 10.1631/FITEE.2100407.

Lu D., Tian Y., Liu V. Y., Zhang Y. (2015). The performance of the smart cities in China - A comparative study by means of self-organizing maps and social networks analysis Sustainability. (7(6)). 7604-7621. doi: 10.3390/su7067604.

Meijer A., Bolívar M. P. R. (2016). Governing the smart city: a review of the literature on smart urban governance International Review of Administrative Sciences. (82(2)). 392-408. doi: 10.1177/0020852314564308.

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD) Overview of National Smart City Pilots. 5 January 2021. Retrieved May 01, 2024, from http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/wjfb/202101/t20210105_251544.html

Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) National Innovation City. 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2024, from https://www.most.gov.cn/eng/programmes1/200610/t20061030_36224.htm

National Bureau of Statistics Local Government Debt Audit Results. 2022. Retrieved April 28, 2024, from http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/

National People\'s Congress The 13th Five Year Plan, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2024, from https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/policies/202105/P020210527785800103339.pdf

National People\'s Congress The 14th Five Year Plan, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2024, from https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/2021fs06-national-14th-five-year-plan-20210610-e.pdf

National People\'s Congress The12th Five Year Plan, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2024, from https://english.www.gov.cn/12thFiveYearPlan/

Todaro, D. (2024). Public Sector AI Applications in Shanghai Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

World Bank Urban Development OverviewWorld Bank, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment

Wu J., Lin K., Sun J. (2024). The impact of smart city construction on urban energy efficiency: evidence from China Environment, Development and Sustainability. doi: 10.1007/s10668-024-04916-8.

Xinhua China names 500 model smart cities after 5 years of exploringXinhua. 29 December 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2024, from http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-12/29/c_135935437.htm

Xinhua China outlines 14th Five-Year Plan blueprint, eyes 2035 visionXinhua. 12 March 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2024, from https://english.news.cn/20210312/c9c194c1c5194079aee97f4da97b44c0/c.html

Xinhua China rolls out plan for new infrastruction list with 5G, AI leading the wayXinhua. 23 April 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2024, from http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-04/23/c_138999670.htm

Xu W., Xu J. (2024). Financing sustainable smart city Projects: Public-Private partnerships and green Bonds Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments. 103699.

Yin C., Xiong Z., Chen H., Wang J., Cooper D., David B. (2015). A literature survey on smart cities Science China Information Sciences. (58(10)). 1-18.

Yuan L. Three problems that impede the development of smart cities in ChinaDutchCham White Paper, 2019. Retrieved May 01, 2024, from Retrieved from: https://dutchchamber.cn/sites/default/files/white_paper_-_smart_cities.pdf

Zen Soo Z. China’s quest for smart cities faces challenges over growth, coordinationSouth China Morning Post. 14 September 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2024, from https://www.scmp.com/tech/enterprises/article/2164670/chinas-quest-smart-cities-faces-challenges-over-growth

Zhang Youzhi, Liu Yinke, Zhao Jing, Wang Jingyi. (2023). Smart city construction and urban green development: empirical evidence from China Scientific Reports. (13(1)). 1-17. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-44061-2.

Zou X. (2023). Eco-City Development in China: International Perspective and Comparaison Singapore: Springer.