The impact of digital identity on the labor supply of the young elderly: an empirical study from China

Zhang Xiaoxia1,2![]()

1 Institute of Education and Arts, Ningde Normal University, ,

2 Tomsk State University, ,

Скачать PDF | Загрузок: 72

Статья в журнале

Экономика труда (РИНЦ, ВАК)

опубликовать статью | оформить подписку

Том 11, Номер 7 (Июль 2024)

Эта статья проиндексирована РИНЦ, см. https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=68533871

Аннотация:

In the digital age, digital identity has become an important basis for people to conduct socio-economic activities. However, for older people, they may face challenges and troubles with digital identity. Therefore, it is of great theoretical and practical significance to study the impact of digital identity on the labour supply of young elderly (The elderly population with a biological age of 55-70 years and with the ability and willingness to work). This paper explores the mechanism, factors and degree of influence of digital identify identification on the labour supply of young elderly through the method of empirical research. The results of the study show that the digital identify identification of young elderly has a significant positive impact on their labour supply. As a result, this study provides a new reference for other scholars\' research on the digital divide in old age; it also provides a basis for the government, enterprises and families to build a synergistic mechanism to eliminate the digital divide in old age.

Ключевые слова: young elderly, digital identity identification, digital divide, labour supply

Финансирование:

FUNDING:

The study was financially supported by the research project of the National Social Science Fund of China No. 23XJYY009.

JEL-классификация: J14, J21, J22, J24, J26

Introduction

In recent years, the new generation of Internet information technology has been rapidly updated and iterated. It has not only promoted digital transformation in the production field such as intelligent production methods, digitalization of industrial forms, changes in industrial organization platforms, and the creation of new work models and new jobs. It also promotes digital transformation in the areas of life such as smart healthcare, digital learning, smart transport, smart home, online socializing and online shopping. At the same time, the traditional lifestyles of the elderly have been impacted or subverted, resulting in the passive integration of many elderly into digital social life. As a result, labour supply at the intersection of population ageing and digital transformation has become the focus of research in various countries.

In China, due to a number of factors such as rapid aging of the population, the lag in the construction of the social security system and the urban-rural dichotomy, labour supply is not only an important way of social participation for the young elderly (the retired elderly between 55 and 70 years of age), but it also has a positive impact on the improvement of the economic situation, social circle, physical health and psychological well-being of the young elderly (Zhang X.X., and Nedospasova O., 2023) [1]. An analysis of the existing literature reveals that scholars' findings on the evolution and scope expansion of identity theory indicate that human identity changes significantly with changing times (technological innovations, economic scale, development patterns, etc.), which leads to the emergence of new identities; while other scholars have confirmed that Internet use has a significant impact on labour participation, community activities, volunteerism and family care. Based on these two theoretical perspectives, the authors propose a brand-new concept, digital identity, which provides a new way of thinking to unravel the mystery that constrains the labour supply of young seniors. Accordingly, the authors propose four hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Internet use has a positive effect on the labor supply of the young elderly.

Hypothesis 2: The higher the frequency of Internet use, the greater the possibility of labor supply for the young elderly.

Hypothesis 3: The social security system has an impact on the labor supply of the young elderly.

Hypothesis 4: There is significant urban-rural heterogeneity in the labor supply of the young elderly.

In order to test these four hypotheses, firstly, the mechanism of the identification of the digital identity of the elderly was dissected from the perspectives of triggering, catalysing, and shaping, and its mechanism of action on the labour supply of the elderly; then, a number of proxy variables were selected from the CGSS2017 database and the above hypotheses were verified by using the Zero-Inflated Poisson model in the Stata 17 software.

Literature review

Studies related to identity theory. Some philosophers and psychologists have argued that a person's identity is shaped by his (or her) interactions with others and the social environment (Busacchi V. and Martini G., 2021) [2]. Identity is an understanding of ‘who I am’ (Glover J., 1988; Ludwig A., 1997) and a reflection on ‘the sense of belonging to particular attributes’ (Alanen L., 1999) [3-5]. It is the ability to recognise ‘common features with others or groups’ (Hall S., 1996) [6], which develops gradually through internalisation of cultural and linguistic rules and interactions (Mead G.H., 1934) [7]. Individuals experience opposition, conflict and integration in this process, gradually recognising their freedom and independence (Hegel, 1807) [8]. In addition, identities are dynamic systems that change and evolve after formation (Freud S., 1949; Cordon L., 2018) [9-10]. Sociological psychologists divide identity into self-identity and social identity. Self-identity is concerned with the confirmation of individual identity, the theory of self-development suggests that the self develops gradually from physiological to social to psychological (Allport G., 1961) [11], and the theory of self-identity suggests that its formation is a central task of adolescence, a mental process of convincing oneself that I am one and not the other (Erikson E., 1998) [12]; and social identity explains the formation of the individual's identification with the group (Tajfel H. and Turner J.C., 1979). Social identity theory refers to identification based on individual qualities as personal identity and identification based on group identity as social identity (Turner J.C. et al., 1987; Hogg M.A., 2016) [13-15]. In addition, some scholars of communication and economics have argued that technological advances, political upheavals, and economic development have prompted people to adjust or integrate their identities in accordance with the macro-environment (Meyrowitz J., 2015; Breakwell G., 2015; Akerlof G.A., Kranton R.E., 2010) [16-18], which, in turn, has led to a reshaping of societal roles and behavioural norms ( Kranton R.E., 2016) [19]. Clearly, as society develops, the understanding of identity evolves.

A study of the impact of Internet use on the elderly. Since the 1980s, the rapid development and diffusion of Internet communication technologies have driven the global economic and social transition to digitalisation, changing the production and life scenarios of social groups (Castells M., 2006) [20]. The application of the Internet provides new opportunities for older people's identity. On the one hand, Internet use is beneficial for older people's physical and mental health, helping with self-health assessment (Tavares A.I., 2020) [21], increasing the frequency of physical activity and thus improving physical health (Nakagomi A. et al., 2022) [22]; enhancing older people's connectedness (Wang H. and Wellman B., 2010 ) [23], reducing loneliness (Patrícia S. et al., 2022) [24], and enhancing life satisfaction (Du P., 2020) and mental health (Shelia R. et al., 2014) [25-26]. In addition, Internet use improves e-health literacy among older adults, which helps prevent and manage chronic diseases (Li P. et al., 2023) [27]. On the other hand, the Internet has become an important tool for older adults to continue socialising (Chen X.L., 2015) [28]. Through the Internet, older adults enhance information acquisition and cognitive abilities (Kamin S. and Lang F., 2020) [29], broaden social networks (Barbara N. and Jaime F., 2015) [30], and accumulate social capital (Barbosa B. et al., 2018) [31]. Modern technology training helps to improve the psychosocial environment of older adults (Taylor M. and Bisson J., 2021) [32] and enhance human capital, self-efficacy, and motivation for social participation (Jin Y. and Zhao M., 2019) [33]. With increased frequency of Internet use and skills, older adults become more socially active (Grigoryeva I. and Kelasev V., 2016) [34], and re-employment and community activities become important ways for older adults to realise their self-worth (Li B. et al., 2023) [35].

However, the negative effects of digital transformation on the elderly cannot be ignored. On the one hand, the elderly are affected by objective factors such as physiological decline, relatively low level of education, reduced interest in accepting new things, insufficient mastery of digital skills, and fewer training avenues, which in turn creates psychological resistance or rejection of digital use (Berkowsky R., 2018) [36]. On the other hand, a certain degree of internal powerlessness exists among the elderly due to the faster updating of digital technology, the low degree of aging of digital devices and software, the existence of loopholes in digital security, and the difficulty in distinguishing the authenticity of digital content (Gulbrandsen K. & Sheehan, M., 2020) [37]. Both of these aspects significantly exacerbate the digital divide among the elderly (Friemel, 2016) [38].

In conclusion, multidisciplinary research has shown that identity shifts with changes in the objective world, emphasising the interaction between society and self. It is clear that the widespread use of digital technology will lead them to a new identity, i.e. digital identity identification.

Theoretical mechanisms and research hypotheses

So, what exactly is digital identity identification? This article defines digital identity identification as: personal display in digital society (such as showing your interests, opinions, etc. on platforms such as social media, blogs, forums, etc.), social interaction (such as communication, comments, likes, sharing, etc.), Internet behavior (such as search, shopping, reading, etc.), community ownership (such as adding online interest groups, communities, etc.) and other online activities formed by digital social identity (or character recognition) formed. It can reflect personal characteristics such as personal interests, values, social circles, etc., and can also reflect the brand image and value proposition of an organization or group. Moreover, with the continuous iteration of digital technology, people's digital identity will also change further.

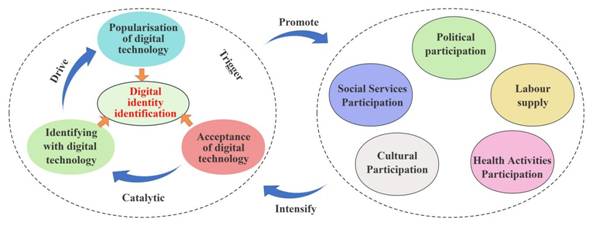

(1) The spread of digital technology as a trigger for the identity crisis of the elderly. When individuals or groups are faced with new circumstances, challenges or pressures, they may begin to question their identity, feel confused, anxious or lost, and lead to significant changes in mood and behaviour. It is only by resolving psychological conflicts that self-identity can be achieved and the desired inner confidence can be gained (Erikson E., 1968) [39]. Currently, the rapid development of digital technology brings convenience and innovation to people's lives, but it also brings challenges to the elderly. Older people may feel marginalised due to technological complexity, lack of relevant knowledge and skills, and cultural differences. Learning and adapting to new technologies can be a serious challenge for the elderly, and this identity crisis may have a negative impact on their self-esteem and mental health (Matthews S., 2008) [40]. It can be seen that the popularity and widespread use of digital technology has triggered an identity crisis among the elderly.

(2) Acceptance of digital technology as a catalyst for the digital identity identification of the elderly. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) suggests that an individual's acceptance and use of new technology is primarily influenced by perceived utility and perceived ease of use (Davis, F., 1989) [41]. In the current rapid transformation of the world to a digital society, the living environment and social connections of the elderly are also covered by digital technologies (Shalagina G. & Shalagin S., 2022) [42]. For the elderly, on the one hand, acceptance and use of digital technology is only possible if they perceive it to be of practical value to their daily lives. On the other hand, the ease of learning and operating digital technologies is a key consideration for acceptance and use by the elderly. In addition, factors such as personal attitudes, social relationships and experiences may also affect their acceptance and use of digital technologies. In this scenario, acceptance of digital technology plays a catalytic role in the digital identity identification of the elderly.

(3) Identifying with digital technology as a shaping agent of digital identity identification for the elderly. Information Technology Identity (ITI) theory suggests that individuals view information technology as a self-concept over a long period of interaction with it (Carter M., 2012) [43]. As Information Technology Identity is not only a product of an individual's interaction history, but also an important force that influences his/her thinking and behaviour. Typically, IT identity affects the digital identity of the elderly through three dimensions: relevance, emotional engagement, and dependence. First, relevance refers to the elderly's integration of information technology into their self-concept and their identification with its importance in their lives. Second, affective engagement refers to seniors' emotional attachment to information technology, which motivates them to use digital technology more actively. Finally, dependence implies that seniors rely more on digital technology to fulfil a wide range of social activities. It is clear that information technology identity plays a significant role in shaping the digital technology identity of the elderly through relevance, emotional engagement and dependence (Emelyanova O., 2023) [44] and in order to create a solid foundation for the digital identity identification of the elderly.

Source: drawn by author

Figure 1 - The mechanical flowchart of the elderly digital identity identification and social participation

(4) The labor supply of the elderly is an important way of digital identity identification. Numerous studies have shown that economic pressures are the main reason why elderly re-enter the labour market. This has led some elderly to work to cope with the decline in quality of life caused by reduced income and lower pension replacement rates. Currently, with the wide application and constant updating of digital technology and network communication, people's needs for information acquisition, dissemination and utilisation in the real society and digital virtual world have gradually merged, initially forming a digital society (Wang F. & Guo L., 2022) [45]. On the one hand, the spread of digital technology has provided an important foundation for the labour supply of elderly, allowing them to use digital technology to find work or conduct business from home via the Internet. On the other hand, the development of the digital economy has created many new occupations and more flexible working patterns, enabling elderly to better balance work and family life. It is evident that labour supply under economic pressure has become an intrinsic driver of elderly's digital identity identification. Overall, the labour supply of elderly in the digital age not only reflects their adaptation and acceptance of new things, but also intuitively reflects their digital identity identification.

Data sources, variable selection and model construction

Analyzing the impact of digital identity on the labour supply of low-income older people requires the collection of survey data on their acceptance, proficiency and evaluation of digital technology, as well as data on labour hours, income, and personal, family and social characteristics (George B., 2019) [47]. Therefore, the authors chose the ‘Chinese General Social Survey 2017)’ data set, which has more than 12,500 valid samples, contains more than 780 variables, and includes a large amount of data on Internet usage. Since the survey respondents in this paper are limited to 55 to 70 years old, after removing the missing values, a total of 3464 valid samples were obtained.

(1) Dependent variables. Because the labor supply is the decision of the working hours that the family or individual is willing to provide under certain wage rates ( Hicks J.R., 1963 ) [48]. Therefore, we select the CGSS2017 data set about ' how many hours do you usually work per week? ' to measure the labor supply situation of the young elderly, named Labor Supply (LS). According to the survey data, the average weekly working hours of employees in Chinese enterprises in 2016 was 46.1 hours, but the working hours of residents in rural areas were generally more than 65 hours [49] . Therefore, the average working time of the young elderly is about 56 hours per week.

(2) Independent variables. As it can be seen from the previous section, digital identity identification is the result of an individual's acceptance and identification with digital technology, so the questionnaire items related to digital identity identification in the CGSS2017 data set were selected. It mainly includes Online social interaction, Online Self-Presentation, Online rights protection, Online Leisure and Entertainment, Online Information Access and Online Trading ( see Table 1 ). The answers to these six questions are all composed of ordered data of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, representing 'never', 'rarely', 'sometimes', 'often' and 'always ‘respectively.

Table 1 Independent variable related content

|

Investigation

item

|

Variable name

|

|

1. How often do you go online to communicate with people via Email, QQ, WeChat, Skype, etc.?

|

Online social interaction (OSI)

|

|

2. How often

do you go online to record and share your moods on WeChat, Qzone, Weibo and

other platforms?

|

Online Self-Presentation

(OSP)

|

|

3. How often

do you go online for actions such as online

advocacy?

|

Online rights protection

(ORP)

|

|

4. How often do you go online for online leisure and entertainment such as games, music and videos?

|

Online Leisure and Entertainment (OLE)

|

|

5. How often do you go online for information gathering, news browsing and other

information access activities?

|

Online Information Access (OLA) |

|

6. How often do

you go online for business transaction activities such as online

transfers, payments, and online shopping?

|

Online Trading (OT) |

(3) Control variables. In terms of personal characteristics, gender, age, physical health status(PHS), educational level(EL), and Marital status(MS) are the factors that labour supply of the elderly is based on (French E., & Jones J. ,2017 ) [50]. Subjective well-being is an important manifestation of the mental health status of the elderly, named Mental Health status(MHS); reading in the leisure time of the elderly is an effective way to improve their cognitive ability (Heckman J. et.al., 2006) [51], named Cognitive Ability(CA). For family characteristics, the number of children of the elderly was used as a proxy variable for the family size of the elderly, named Children.The income data of the elderly's family throughout the year was used to measure the family economic status (HES). In terms of social characteristics, the subjective perception of socioeconomic status was used to measure the judgement of social class position and identity (Zheng L. & Xu M., 2022) [52] , named socio-economic stratum (SES). The frequency of the elderly's participation in offline social interaction activities is used to measure their social capital status, named Social Capital (SC). Social security such as Medicare and Pension have important impacts on the retirement decisions of the elderly (Ceni R., 2017; French E. & Jones J., 2011) [53-54], named Medical insurance(MI) and Pension, respectively.In addition, the long-term place of residence is used to measure the difference in the labour supply of the elderly in urban and rural areas, named Living Place (LP).

From the perspective of the selected data type, since the dependent variable Labor Supply ( LS ) belongs to the count variable, the main value is [ 0, 1, 2, ... n ], and the proportion of 0 is more than 74.4 %. Therefore, the Zero-Inflated Poisson (ZIP) model is used for regression analysis. Since the goal of the ZIP model is to estimate the zero-inflated probability and the mean parameter of the count part, the distribution of the count data and the probability of occurrence of the zero value are predicted. By adding the independent variable Xi ( i = 1, 2, ..., n ) and the control variable Zj ( j = 1,2, ..., m ), the probability function can be expressed as :

![]()

In equation (1), Y is the count data of an event, P(Y=0) is the probability that the event does not occur, and P(Y=y) is the probability that the event occurs y times. α is the intercept of the zero- inflated portion, β is the coefficient of the independent variable X, γ is the coefficient of the control variable Z, λ is the parameter of the Poisson distribution, e is the base of the natural logarithm, y is the count value, and y! indicates the factorial of y.

Therefore, the function after adding dependent and control variables can be expressed as:

In Equation (2), β is the coefficient of the independent variable Xi and γj is the coefficient of a number of control variables such as Genderj , Agej , PHSj , ELj , CAj , MSj and MHSj .

Empirical analyses

Table 2 shows that the median weekly labour supply of the low elderly is about 8.5 hours. They frequently use life-related digital technologies such as OSI, OSP, OLE, and OLA, but less often use complex ORP and OT.In terms of individual characteristics, the median age of the young elderly is 62.6 years old, they are in good health, and most of them are married but with lower education and cognitive ability. In terms of family characteristics, the median number of children was about 2, and the median annual income was about $60,698. In terms of social characteristics, they have a median perceived socioeconomic class of 2.14, a median social capital of about 2.7, a preference for offline socialising, a median of 0.93 and 0.81 for having health insurance and pension respectively, and a high proportion of urban permanent residents.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics of variables

|

Variable

|

Obs

|

Mean

|

Std.

dev. |

Min

|

Max

|

Instructions

|

|

Labour Supply (LS)

|

3,464

|

8.533

|

16.66

|

0

|

56

|

Number of hours worked per week

|

|

Online

social interaction (OSI)

|

3,464

|

2.138

|

0.563

|

1

|

5

|

1,

2, 3, 4, 5, indicating the

low to high frequency of digital technology use by elderly individuals. |

|

Online Self-Presentation

(OSP)

|

3,464

|

2.032

|

0.392

|

1

|

5

| |

|

Online rights

protection (ORP) |

3,464

|

1.947

|

0.292

|

1

|

5

| |

|

Online

Leisure and

Entertainment (OLE) |

3,464 |

2.101 |

0.501 |

1 |

5 | |

|

Online Information

Access (OLA) |

3,464

|

2.140

|

0.574

|

1

|

5

| |

|

Online Trading (OT)

|

3,464

|

1.989

|

0.388

|

1

|

5

| |

|

Gender

|

3,464

|

0.464

|

0.499

|

0

|

1

|

Female = 0, Male = 1

|

|

Age

|

3,464

|

62.571

|

4.247

|

55

|

70

|

Aged 55-70

|

|

Physical health status (PHS)

|

3,464

|

3.050

|

1.083

|

1

|

5

|

1-5 indicates poor

to good

|

|

Educational level (EL)

|

3,464

|

3.893

|

2.352

|

1

|

13

|

1- 13 indicates low to high

|

|

Cognitive Ability (CA)

|

3,464

|

2.029

|

1.464

|

1

|

5

|

1

to 5 indicates low to

high

|

|

Marital status (MS)

|

3,464

|

0.789

|

0.408

|

0

|

1

|

Unmarried = 0,

Married = 1

|

|

Mental Health

status

(MHS) |

3,464

|

2.344

|

3.290

|

0

|

10

|

1- 10 indicates poor to good

|

|

Children

|

3,464

|

1.979

|

1.082

|

0

|

5

|

Number of children

|

|

Household Economic Status (HES)

|

3,464

|

60698

|

123330

|

0

|

5,000,000

|

0~5000000 RMB

|

|

Social-economic stratum

(SES)

|

3,464

|

2.140

|

0.895

|

1

|

5

|

1-5 indicates low

to high

|

|

Social Capital (SC)

|

3,464

|

2.703

|

1.125

|

1

|

5

|

1-5 indicates low

to high

|

|

Living Place (LP)

|

3,464

|

0.588

|

0.492

|

0

|

1

|

Rural=0, Urban=1

|

|

Medical Insurance (MI)

|

3,464

|

1.061

|

0.256

|

0

|

1

|

No = 0, Yes

= 1

|

|

Pension

|

3,464

|

1.173

|

0.405

|

0

|

1

|

No = 0, Yes

= 1

|

In Table 3, Model (2) shows that Online Self-Presentation (OSP) has a significant positive effect on the labour supply of the young elderly (p-value = 0.006).Online Self-Presentation refers to the presentation of one's abilities, experiences and achievements through platforms such as the Internet and social media. For the lower-aged elderly, online self-presentation can increase their visibility and influence, and share their experience and wisdom with others. This can not only increase the self- confidence and self-esteem of the young elderly, but also stimulate their creativity and motivation to participate in social activities. Model(4) shows Online Leisure and Entertainment (OLE) positively impacts younger elderly labour supply (p-value=0.038). OLE provides relaxation, reduces pressure, and enhances mental health, increasing labour motivation. It also offers social interaction, reducing loneliness and expanding social support. Cognitive activities in OLE maintain cognitive function, benefiting labour participation. Model(6) shows Online Trading (OT) positively affects younger elderly labour supply (p-value=0.000). Digital technology offers new job opportunities for older adults to use their skills online, making work hours flexible and improving quality of life. It enhances social participation and mental health while providing opportunities to learn new digital skills.

The positive effects of Model (2), Model (4) and Model (6) on the labour supply of the young elderly suggest that the higher the frequency of the young elderly's use of digital technology the higher the probability of their labour supply. At a deeper level, the process of accepting and identifying with digital technologies such as Online Self-Presentation, Online Leisure and Entertainment, and Online Trading is a concrete manifestation of the digital identity identification of the young elderly. Moreover, as the digital identity of the young elderly increases, the likelihood of their labour supply increases significantly. These regression results also show that the authors' hypotheses 1 and 2 are valid.

Table 3 - Descriptive statistics of variables

|

Variable

|

Model(1)

|

Model (2)

|

Model (3)

|

Model (4)

|

Model (5)

|

Model (6)

|

Model (7)

|

|

OSI

|

OSP

|

ORP

|

OLE

|

OLA

|

OT

|

DII

| |

|

LS

|

0.0096

|

0.0439**

|

-0.0017

|

0.0290*

|

-0.0002

|

0.065***

|

0.009*

|

|

Gender

|

0.086***

|

0.087***

|

0.085***

|

0.086***

|

0.085***

|

0.087***

|

0.086***

|

|

Age

|

-0.0038*

|

-0.0039*

|

-0.0038*

|

-0.0037*

|

-0.0038*

|

-0.0042**

|

-0.0038*

|

|

PHS

|

0.045***

|

0.045***

|

0.045***

|

0.046***

|

0.045***

|

0.046***

|

0.045***

|

|

EL

|

-0.0088*

|

-0.0093**

|

-0.0083*

|

-0.0093**

|

-0.0083*

|

-0.0097**

|

-0.0099**

|

|

CA

|

-0.003

|

-0.003

|

-0.002

|

-0.003

|

-0.002

|

-0.003

|

-0.003

|

|

MS

|

0.080***

|

0.079***

|

0.080***

|

0.079***

|

0.080***

|

0.080***

|

0.079***

|

|

MHS

|

0.0048**

|

0.0049**

|

0.0046*

|

0.005**

|

0.0045*

|

0.0046*

|

0.005**

|

|

Children

|

-0.001

|

-0.0004

|

-0.001

|

-0.0006

|

-0.001

|

-0.0007

|

-0.0007

|

|

HES

|

6.49E-08

|

6.64E-08

|

6.60E-08

|

6.07E-08

|

6.64E-08

|

2.34E-08

|

5.72e-08

|

|

SES

|

-0.006

|

-0.006

|

-0.006

|

-0.006

|

-0.006

|

-0.007

|

-0.006

|

|

SC

|

-0.011*

|

-0.012*

|

-0.012*

|

-0.011*

|

-0.011*

|

-0.010*

|

-0.0115*

|

|

LP

|

0.095***

|

0.096***

|

0.096***

|

0.094***

|

0.096***

|

0.097***

|

0.094***

|

|

MI

|

-0.076***

|

-0.077***

|

-0.076***

|

-0.076***

|

-0.076***

|

-0.076***

|

-0.077***

|

|

Pension

|

-0.028

|

-0.029

|

-0.028

|

-0.029

|

-0.027

|

-0.027

|

-0.029

|

|

inflate

_cons |

1.067***

|

1.067***

|

1.067***

|

1.067***

|

1.067***

|

1.067***

|

1.067***

|

Source: Authors' calculations based on CGSS2017 database

In terms of individual characteristics, older men are more likely than women to have access to labour opportunities because of their digital identity. Good physical and mental health contributes to young elderly's labour supply; married people are more likely to have access to labour supply than unmarried people, while age and education are the main barriers. Although the number of children has a negative effect on labour supply, it is not significant; household income has a positive effect. Lack of social resources significantly limits labour supply, and having public health insurance and a pension reduces the likelihood of labour supply, with health insurance having a particularly strong effect. young elderly living in urban areas are more likely to participate in the labour force than in rural areas, as there are more jobs in urban areas, which supports hypotheses 3 and 4.

In Table 4, the Incident Rate Ratio (IRR) of the digital identity identification of the young elderly for their labor supply shows that for every unit increase in OSP, the possibility of their labor supply increases by about 4.5 %. For every unit increase in OLE, the possibility of labor supply increases by about 2.9 %. For every unit increase in OT, the possibility of labor supply increases by about 6.7 %.

Table 4 - Incident rate ratio of digital identity identification of young elderly on their labour supply

|

Variable

|

OSP

|

OLE

|

OT

|

DII

|

|

IRR

|

1.045

|

1.029

|

1.067

|

1.0091

|

Digital Identity Identification of the young and old is a combined result of multiple digital technologies. The regression results of the composite variable Digital Identity Identification (DII) better show its effect on labour supply. The regression results of Model (7) in Table 2 show that DII has a significant positive effect on the labour supply of the under-aged elderly (p-value = 0.001). for every 1 unit increase in DII, the likelihood of labour supply increases by about 0.91% (see Table 4). This proves the robustness of the model and the validity of the hypothesis.

Conclusions

Empirical results show that Online Self-Presentation, Online Leisure and Entertainment, and Online Trading significantly promote young elderly labor supply. Digital technology acceptance enhances their digital identity, impacting social labor participation. Although OSI, Online Information Access, and Online Rights Protection are crucial for digital identity and social participation, their regression results lacked statistical significance, possibly due to sample size and data processing issues. Future studies should design better questionnaires and ensure adequate sample size and quality for reliable data.

At present, the development of the digital society is irreversible, and the young elderly are bound to accept a variety of digital technologies and gradually agree with the positive effects of digital technology, thus realizing their digital identity identification. Moreover, the process of the young elderly's digital identity identification will also trigger significant changes in their social participation behaviors and approaches. Therefore, in order to avoid the young elderly becoming marginalized in the digital society, they should be helped to quickly adapt to and accept their digital identity identification. Specifically, the government should clear the obstacles for the young elderly to cross the digital divide through policy support, improving infrastructure, and building a digital literacy education system; while enterprises should pay attention to the age-adapted modification of digital hardware and software to adapt to the usage needs of the young elderly. The younger generation in the family should proactively convey digital thinking, digital skills, and cybersecurity awareness to the young elderly, inspire confidence in the use of digital technology, and drive the young elderly to better adapt to digital life.

Источники:

2. Busacchi V., Martini G. Personal identity between philosophy and psychology: a perpetual metamorphosis?. - Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

3. Glover Jonathan I: The Philosophy and Psychology of Personal Identity. - New York, N.Y., USA: Penguin Books, 1988.

4. Ludwig A. M. How Do We Know Who We Are?. - Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. – 11 p.

5. Alanen Lilli Intuition, Assent and Necessity: The Question of Descartes’s Psychologism. / Acta Philosophica Fennica 64: Norms and Modes of Thinking in Descartes, Tuomo Aho and Mikko Yrjönsuuri (eds). - Helsinki: Philosophical Society of Finland, 1999. – 99–125 p.

6. Hall S. Introduction: Who Needs Identity? Questions of Cultural Identity. / Eds. Stuart Hall and Paul du Gay. - CA: Sage Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications Ltd., 1996. – 1-17 p.

7. Mead G.H. Mind, Self, and Society. / Translated by Zhao, Y. - Shanghai: Translation Publishing House, 1997. – 118-125 p.

8. Hegel G. W. F. Self-consciousness: Lordship and Bondage. / in Phenomenology of Spirit by Georg W. F. Hegel; J. B. Baillie, Trans. - Oxford University Press, 1807. – 111- 179 p.

9. Freud S. An outline of psychoanalysis. - New York: Norton, 1949. – 127 p.

10. Cordon L. Freud’s Psychoanalytic Theory. / In: Shackelford, T., Weekes-Shackelford, V. (eds) Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. - Springer, Cham, 2018.

11. Allport G.W. Pattern and growth in personality. - New York: Holt. Rinehart and Winston, 1961. – 530-550 p.

12. Erickson E.H. Identity: Adolescence and crisis. - Hangzhou: Zhejiang Education Press, 1998. – 19 p.

13. Tajfel H., Turner J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. / In: Austin, W.G..Worchel, S. (Eds.). The social psychology of intergroup relations. - Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole, 1979. – 33- 47 p.

14. Turner J.C., Hogg M.A., Oakes P.J., Reicher S.D., Wetherell M.S. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. - Oxford: Blackwell, 1987.

15. Hogg M. A. Social identity theory. / In S. McKeown, R. Haji, and N. Ferguson(Eds.), Understanding peace and conflict through social identity theory: Contemporary global perspectives. - Springer International Publishing, 2016. – 3– 17 p.

16. Meyrowitz J. No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior. - Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

17. Breakwell G. Identity Process Theory. - Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. – 250-268 p.

18. Akerlof G.A., Kranton R.E. Identity Economics: How Our Identities Shape Our Work, Wages, and Well-Being. - Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

19. Kranton R.E. Identity Economics // American Economic Review. – 2016. – № 106(5). – p. 405-409. – doi: 10.1257/aer.p20161038.

20. Castells M. The Power of Identity. - Beijing: Social Science Literature Publishing House, 2006.

21. Tavares A.I. Self-assessed health among older people in Europe and internet use // International Journal of Medical Informatics. – 2020. – № 141. – p. 104240. – doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104240.

22. Nakagomi A., Koichiro Shiba, Ichiro Kawachi, Kazushige Ide, Yuiko Nagamine, Naoki Kondo, Masamichi Hanazato, Katsunori Kondo Internet Use and Subsequent Health and Well-being in Older Adults: аn Outcome-wide Analysis // Computers in Human Behavior. – 2022. – № 130. – p. 107156.

23. Wang H., Wellman B. Social connectivity in America: Changes in adult friendship network size from 2002 to 2007 // American Behavioral Scientist. – 2010. – № 53(8). – p. 1148-1169. – doi: 10.1177/0002764209356247.

24. Silva P., Matos A. D., Martinez-Pecino R. Can the internet reduce the loneliness of 50+ living alone? // Information, Communication & Society. – 2020. – p. 1–17. – doi: 10.1080/1369118x.2020.1760917.

25. Du Peng, Wang Bin How does the Internet use affect the life satisfaction of young elderly people in China? // The Population Study. – 2020. – № 44 (4). – p. 3- 17.

26. Shelia R. Cotten, George Ford, Sherry Ford, Timothy M. Hale Internet Use and Depression Among Retired Older Adults in the United States: a Longitudinal Analysis // The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. – 2014. – № 69(5). – p. 763-771. – doi: 10.1093/ geronb/gbu018.

27. Li P., Zhang C., Gao S., Zhang Y., Liang X., Wang C., Zhu T., Li W. Association Between Daily Internet Use and Incidence of Chronic Diseases Among Older Adults. Prospective Cohort Study // J. Med Internet Res. – 2023. – № 25. – p. e46298. – doi: 10.2196/46298.

28. Chen X.L. On the Internet and the continued socialisation of the elderly // Press Circles. – 2015. – № 17. – p. 4-8. – doi: 10.15897/j.cnki.cn51- 1046 / g2.2015.17.002.

29. Kamin S. T., Lang F. R. Internet Use and Cognitive Functioning in Late Adulthood: Longitudinal Findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) // The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. – 2020. – № 75(3). – p. 534-539. – doi: 10.1093/geronb/ gby123.

30. Neves Barbara, Fonseca Jaime Latent Class Models in action: bridging social capital and Internet usage // Social Science Research. – 2015. – № 50. – doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.11.002.

31. Barbosa Neves B., Fonseca J.R.S., Amaro F., Pasqualotti A. Social capital and Internet use in an age-comparative perspective with a focus on later life // PLoS ONE. – 2018. – № 13(2). – p. e0192119. – doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192119.

32. Taylor Mary, Bisson Jennifer Improving the psychosocial environment for older trainees: technological training as an illustration // Human Resource Management Review. – 2021. – № 32. – p. 10082. – doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2020.100821.

33. Jin Yongai, Zhao Menghan Internet Use and Active Aging of Chinese Elderly People -- based on the analysis of the 2016 China Elderly Social Tracking Survey Data // Journal of Demographic Studies. – 2019. – № 41 (06). – p. 44-55. – doi: 10.16405/j.cnki.1004- 129X.2019.06. 004.

34. Grigoryeva I., Kelasev V. Internet in the life of elderly people: intentions and realities // Sociological Studies. – 2016. – № 37(11). – p. 82-85.

35. Li Bing, Yan Zhengwei, Ni Chenxu Impact of Internet use on urban elderly reemployment - Evidence from CLASS data // Labour Economics Research. – 2023. – № 11 (01). – p. 122-144.

36. Berkowsky R. W., Sharit J., Czaja S. J. Factors Predicting Decisions About Technology Adoption Among Older Adults // Innovation in aging. – 2018. – № 2(1). – p. igy002. – doi: 10.1093/geroni/ igy002.

37. Gulbrandsen K.S., Sheehan M. Social Exclusion as Human Insecurity: A Human Cybersecurity Framework Applied to the European High North. / In: Salminen, M., Zojer, G., Hossain, K. (eds) Digitalisation and Human Security. New Security Challenges. - Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2020.

38. Friemel T.N. The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors // New Media and Society. – 2016. – № 18(2). – p. 313-331. – doi: 10.1177/1461444814538648.

39. Erikson E.H. Identity: youth and crisis. - Norton and Co., 1968.

40. Matthews Steve Identity and Information Technology // Information technology and moral philosophy. – 2008. – p. 142-160. – doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511498725.009.

41. Davis Fred, Davis Fred Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology // MIS Quarterly. – 1989. – № 13(3). – p. 319-340. – doi: 10.2307/249008.

42. Шалагина Г. Э., Шалагин С. В. Информационно-коммуникационные технологии и антропная идентичность: взаимовлияние человека и технологий в контексте информационного общества // Вестник Московского государственного областного университета. Серия: Философские науки. – 2022. – № 3. – c. 90-101. – doi: 10.18384/2310-7227-2022-3-90-101.

43. Carter M. Information Technology (IT) Identity: A Conceptualisation, Proposed Measures, and Research Agenda. , 2012.

44. Емельянова О. Б. Личностная идентичность как проблема в свете развития информационно-коммуникативных технологий // Общество: философия, история, культура. – 2023. – № 8(112). – c. 56-64. – doi: 10.24158/fik.2023.8.7.

45. Wang Fang, Guo Lei Study on the system complexity of the digital society // Manage World. – 2022. – № 09. – p. 208-221. – doi: 10.19744/j.cnki.11- 1235/f.2022.0130.

46. George Borjas Labour economics. / 8th Edition, Chapter 2. - McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2019. – 23-80 p.

47. Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS). National Survey Research Center (NSRC) at Renmin University of China. 2017. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn/info/ 1014/1019.htm (дата обращения: 11.06.2024).

48. Hicks J.R. Individual Supply of Labour. / The Theory of Wages. - Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1963.

49. China Labour Statistics Yearbook 2017. The National Bureau of Statistics of China. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: http://cnki.nbsti.net/CSYDMirror/trade/Yearbook/Single/N2021020042?z= Z001 (дата обращения: 11.06.2024).

50. French E., Jones J. Health, Health Insurance, and Retirement: A Survey // Annual Review of Economics. – 2017. – № 9. – p. 383-409. – doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-063016-103616.

51. Heckman James J., Jora Stixrud, Sergio Urzua The Effects of Cognitive and Noncognitive Abilities on Labour Market Outcomes and Social Behavior // Journal of Labour Economics. – 2006. – № 24(3). – p. 411-482. – doi: 10.1086/504455.

52. Zheng Lu, Xu Minxia Inhibition or stimulation?-- Social and economic status perception and risk and financial investment of urban residents // Sociological Review. – 2022. – № 06. – p. 145- 166.

53. Ceni R. Pension schemes and labour supply in the formal and informal sector // IZAJ Labor Policy. – 2017. – № 6. – p. 8. – doi: 10.1186/s40173-017-0085- 1.

54. French E., Jones J. B. The effects of health insurance and self-insurance on retirement behaviour // Econometrica. – 2011. – № 79(3). – p. 693-732. – doi: 10.3982/ECTA7560.

Страница обновлена: 22.11.2025 в 03:11:18

Download PDF | Downloads: 72

Влияние цифровой идентичности на предложение труда молодых пожилых людей; эмпирическое исследование в Китае

Chzhan S.Journal paper

Russian Journal of Labour Economics

Volume 11, Number 7 (July 2024)

Abstract:

В цифровую эпоху цифровая идентичность личности приобретает особую актуальность. Это вопрос весьма сложен для решения у пожилых людей. Изучение влияния цифровой идентичности на предложение труда молодых пожилых людей (граждане в возрасте 55-70 лет, способные и желающие работать) имеет большое теоретическое и практическое значение. В данной работе эмпирически исследуется механизм, факторы и степень влияния цифровой идентификации на предложение труда молодых пожилых людей. Результаты исследования показывают, что цифровая идентичность молодых пожилых людей оказывает значительное положительное влияние на их предложение труда. Полученные результаты создают основу для продолжения исследований о цифровом неравенстве в пожилом возрасте; оно также служит основой для разработки рекомендаций правительству, предприятиям и семьям по синхронизации действий для по устранения цифрового неравенства пожилых.

ФИНАНСИРОВАНИЕ:

Исследование выполнено при финансовой поддержке научного проекта Национального фонда социальных наук Китая № 23XJY009.

Keywords: молодые пожилые люди, цифровая идентичность, цифровое неравенство, предложение труда

Funding:

JEL-classification: J14, J21, J22, J24, J26

References:

Akerlof G.A., Kranton R.E. (2010). Identity Economics: How Our Identities Shape Our Work, Wages, and Well-Being Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Alanen Lilli (1999). Intuition, Assent and Necessity: The Question of Descartes’s Psychologism Helsinki : Philosophical Society of Finland.

Allport G.W. (1961). Pattern and growth in personality New York: Holt. Rinehart and Winston.

Barbosa Neves B., Fonseca J.R.S., Amaro F., Pasqualotti A. (2018). Social capital and Internet use in an age-comparative perspective with a focus on later life PLoS ONE. (13(2)). e0192119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192119.

Berkowsky R. W., Sharit J., Czaja S. J. (2018). Factors Predicting Decisions About Technology Adoption Among Older Adults Innovation in aging. (2(1)). igy002. doi: 10.1093/geroni/ igy002.

Breakwell G. (2015). Identity Process Theory Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Busacchi V., Martini G. Personal identity between philosophy and psychology: a perpetual metamorphosis? (0). Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Carter M. (2012). Information Technology (IT) Identity: A Conceptualisation, Proposed Measures, and Research Agenda

Castells M. (2006). The Power of Identity Beijing: Social Science Literature Publishing House.

Ceni R. (2017). Pension schemes and labour supply in the formal and informal sector IZAJ Labor Policy. (6). 8. doi: 10.1186/s40173-017-0085- 1.

Chen X.L. (2015). On the Internet and the continued socialisation of the elderly Press Circles. (17). 4-8. doi: 10.15897/j.cnki.cn51- 1046 / g2.2015.17.002.

China Labour Statistics Yearbook 2017The National Bureau of Statistics of China. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from http://cnki.nbsti.net/CSYDMirror/trade/Yearbook/Single/N2021020042?z= Z001

Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS)National Survey Research Center (NSRC) at Renmin University of China. 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn/info/ 1014/1019.htm

Cordon L. (2018). Freud’s Psychoanalytic Theory Cham: Springer.

Davis Fred, Davis Fred (1989). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology MIS Quarterly. (13(3)). 319-340. doi: 10.2307/249008.

Du Peng, Wang Bin (2020). How does the Internet use affect the life satisfaction of young elderly people in China? The Population Study. (44 (4)). 3- 17.

Emelyanova O. B. (2023). Lichnostnaya identichnost kak problema v svete razvitiya informatsionno-kommunikativnyh tekhnologiy [Personal identity as a problem in the light of the development of information and communication technologies]. Society Philosophy History Culture. (8(112)). 56-64. (in Russian). doi: 10.24158/fik.2023.8.7.

Erickson E.H. (1998). Identity: Adolescence and crisis Hangzhou : Zhejiang Education Press.

Erikson E.H. (1968). Identity: youth and crisis Norton and Co.

French E., Jones J. (2017). Health, Health Insurance, and Retirement: A Survey Annual Review of Economics. (9). 383-409. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-063016-103616.

French E., Jones J. B. (2011). The effects of health insurance and self-insurance on retirement behaviour Econometrica. (79(3)). 693-732. doi: 10.3982/ECTA7560.

Freud S. (1949). An outline of psychoanalysis New York : Norton.

Friemel T.N. (2016). The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors New Media and Society. 18 (18(2)). 313-331. doi: 10.1177/1461444814538648.

George Borjas (2019). Labour economics McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Glover Jonathan (1988). I: The Philosophy and Psychology of Personal Identity New York: Penguin Books.

Grigoryeva I., Kelasev V. (2016). Internet in the life of elderly people: intentions and realities Sociological Studies. (37(11)). 82-85.

Gulbrandsen K.S., Sheehan M. (2020). Social Exclusion as Human Insecurity: A Human Cybersecurity Framework Applied to the European High North Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hall S. (1996). Introduction: Who Needs Identity? Questions of Cultural Identity CA: Sage Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications Ltd.

Heckman James J., Jora Stixrud, Sergio Urzua (2006). The Effects of Cognitive and Noncognitive Abilities on Labour Market Outcomes and Social Behavior Journal of Labour Economics. 24 (24(3)). 411-482. doi: 10.1086/504455.

Hegel G. W. F. (1807). Self-consciousness: Lordship and Bondage Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hicks J.R. (1963). Individual Supply of Labour London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hogg M. A. (2016). Social identity theory Springer International Publishing.

Jin Yongai, Zhao Menghan (2019). Internet Use and Active Aging of Chinese Elderly People -- based on the analysis of the 2016 China Elderly Social Tracking Survey Data Journal of Demographic Studies. (41 (06)). 44-55. doi: 10.16405/j.cnki.1004- 129X.2019.06. 004.

Kamin S. T., Lang F. R. (2020). Internet Use and Cognitive Functioning in Late Adulthood: Longitudinal Findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. (75(3)). 534-539. doi: 10.1093/geronb/ gby123.

Kranton R.E. (2016). Identity Economics American Economic Review. 106 (106(5)). 405-409. doi: 10.1257/aer.p20161038.

Li Bing, Yan Zhengwei, Ni Chenxu (2023). Impact of Internet use on urban elderly reemployment - Evidence from CLASS data Labour Economics Research. (11 (01)). 122-144.

Li P., Zhang C., Gao S., Zhang Y., Liang X., Wang C., Zhu T., Li W. (2023). Association Between Daily Internet Use and Incidence of Chronic Diseases Among Older Adults. Prospective Cohort Study J. Med Internet Res. (25). e46298. doi: 10.2196/46298.

Ludwig A. M. (1997). How Do We Know Who We Are? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Matthews Steve (2008). Identity and Information Technology Information technology and moral philosophy. 142-160. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511498725.009.

Mead G.H. (1997). Mind, Self, and Society Shanghai: Translation Publishing House.

Meyrowitz J. (1985). No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nakagomi A., Koichiro Shiba, Ichiro Kawachi, Kazushige Ide, Yuiko Nagamine, Naoki Kondo, Masamichi Hanazato, Katsunori Kondo (2022). Internet Use and Subsequent Health and Well-being in Older Adults: an Outcome-wide Analysis Computers in Human Behavior. (130). 107156.

Neves Barbara, Fonseca Jaime (2015). Latent Class Models in action: bridging social capital and Internet usage Social Science Research. (50). doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.11.002.

Shalagina G. E., Shalagin S. V. (2022). Informatsionno-kommunikatsionnye tekhnologii i antropnaya identichnost: vzaimovliyanie cheloveka i tekhnologiy v kontekste informatsionnogo obshchestva [Infocommunication technologies and anthropic identity: the influence of human and technology in the context of the information society]. Vestnik Moskovskogo gosudarstvennogo oblastnogo universiteta. Seriya: Filosofskie nauki. (3). 90-101. (in Russian). doi: 10.18384/2310-7227-2022-3-90-101.

Shelia R. Cotten, George Ford, Sherry Ford, Timothy M. Hale (2014). Internet Use and Depression Among Retired Older Adults in the United States: a Longitudinal Analysis The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. (69(5)). 763-771. doi: 10.1093/ geronb/gbu018.

Silva P., Matos A. D., Martinez-Pecino R. (2020). Can the internet reduce the loneliness of 50+ living alone? Information, Communication & Society. 1–17. doi: 10.1080/1369118x.2020.1760917.

Tajfel H., Turner J.C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Tavares A.I. (2020). Self-assessed health among older people in Europe and internet use International Journal of Medical Informatics. (141). 104240. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104240.

Taylor Mary, Bisson Jennifer (2021). Improving the psychosocial environment for older trainees: technological training as an illustration Human Resource Management Review. (32). 10082. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2020.100821.

Turner J.C., Hogg M.A., Oakes P.J., Reicher S.D., Wetherell M.S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory Oxford: Blackwell.

Wang Fang, Guo Lei (2022). Study on the system complexity of the digital society Manage World. (09). 208-221. doi: 10.19744/j.cnki.11- 1235/f.2022.0130.

Wang H., Wellman B. (2010). Social connectivity in America: Changes in adult friendship network size from 2002 to 2007 American Behavioral Scientist. (53(8)). 1148-1169. doi: 10.1177/0002764209356247.

Zhang X.X., Nedospasova O. (2023). The effect mechanism of identity change on labour participation of Chinese elderly in the digital age Human Progress. 9 (9(1)). 1. doi: 10.34709/IM.191.1.

Zheng Lu, Xu Minxia (2022). Inhibition or stimulation?-- Social and economic status perception and risk and financial investment of urban residents Sociological Review. (06). 145- 166.