Japan’s strategic turn in regional economic integration: from bilateral agreements to mega-regional frameworks

Nazarova D.V.1![]() , Andronova I.V.1

, Andronova I.V.1![]()

1 Российский университет дружбы народов имени Патриса Лумумбы, ,

Скачать PDF | Загрузок: 14

Статья в журнале

Экономические отношения (РИНЦ, ВАК)

опубликовать статью | оформить подписку

Том 15, Номер 3 (Июль-сентябрь 2025)

Эта статья проиндексирована РИНЦ, см. https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=82956637

Аннотация:

Over the past two decades, Japan's trade policy towards regional economic integration has undergone a profound structural transformation. Initially committed to trade liberalization within the framework of the GATT and WTO and guided by careful economic diplomacy, Japan shifted towards bilateralism in the early 2000s before emerging as a central architect in mega-regional trade frameworks such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This article examines the strategic reasons behind this transition, highlights institutional changes in Japan's trade policy, geopolitical ambitions, and changing priorities in the Indo-Pacific region. Based on official government publications, international trade databases, and expert analysis, the authors argue that Japan's trade policy reflects a combination of norm-setting and expanding influence through participation in regional economic integration in a fragmented world order.

Ключевые слова: Japan, bilateralism, multilateralism, regional trade integration, trade policy

JEL-классификация: F02, F14, F15

Introduction

Over the past four decades, Japan’s trade policy has undergone a significant evolution, reflecting both structural changes in the global economy and the country’s shifting strategic priorities. Initially anchored in multilateral institutions such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and its successor, the World Trade Organization (WTO), Japan maintained a cautious stance toward preferential trade agreements, prioritizing non-discriminatory liberalism and export-led industrial growth [20]. However, as regionalism proliferated across East Asia in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Japan gradually reoriented its trade strategy to incorporate bilateral and eventually mega-regional frameworks [6].

This strategic turn was driven by several factors: the rise of China as a regional economic hegemon, the stagnation of multilateral trade liberalization under the WTO, and the competitive liberalization initiatives undertaken by neighboring economies [8]. Japan's initial foray into bilateral Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs), beginning with the Japan–Singapore EPA in 2002, was characterized by cautious liberalization, often excluding sensitive sectors such as agriculture [9]. As these agreements expanded in scope and number—to include countries such as Mexico, Indonesia, and the ASEAN bloc—Japan began to acquire the institutional expertise and diplomatic leverage required to engage in broader regional trade architectures [5].

The turning point came in the 2010s with Japan’s involvement in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations and its subsequent leadership role in salvaging the deal as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) following the U.S. withdrawal in 2017 [16]. In parallel, Japan joined the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a China-backed but ASEAN-led initiative encompassing 15 Asia-Pacific countries, which came into force in 2022 [2]. These developments mark a departure from Japan’s earlier, more reactive trade posture and underscore its ambition to act as both a rule-maker and a stabilizing force in regional trade governance.

This article examines Japan’s evolving regional trade strategy from a historical-institutionalist perspective, focusing on how the shift from bilateralism to mega-regionalism reflects broader geopolitical, economic, and institutional imperatives. It draws on primary government sources, international trade data, and policy analysis to assess the strategic significance of Japan’s trade agreements and the implications for global economic governance in the Indo-Pacific [11]. In doing so, the study contributes to debates on middle-power diplomacy, the resilience of liberal trade norms, and the future architecture of regional economic integration.

1. Historical Background and Multilateral Roots (1980s–1990s)

Japan’s trade policy in the postwar period was fundamentally shaped by the global norms of multilateralism. As a founding contracting party to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), Japan pursued export-led growth within the framework of non-discriminatory trade liberalization [20]. The country emphasized integration into global markets through industrial upgrading and Official Development Assistance (ODA), particularly to Southeast Asia [8]. This period was characterized by what scholars have termed "mercantilist multilateralism", whereby Japan benefited from liberal markets abroad while maintaining protection for key domestic sectors, especially agriculture.

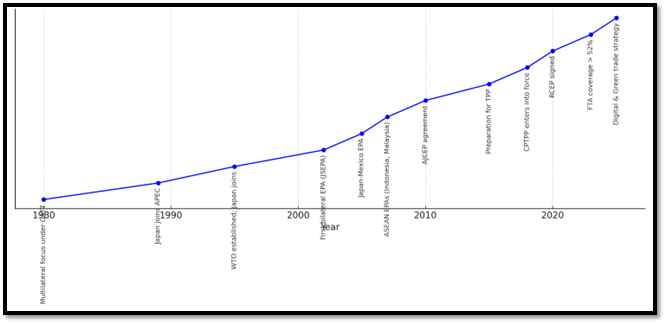

As shown in Figure 1, the trajectory of Japan’s trade engagement during the 1980s and early 1990s remained gradual and cautious. A key turning point was Japan’s participation in the formation of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in 1989, a non-binding forum that institutionalized economic dialogue across the Pacific Rim [9]. APEC enabled Japan to engage in regional economic cooperation without the commitments required under bilateral or plurilateral trade agreements. Importantly, APEC also reflected Japan’s preference for “soft law” approaches that prioritized consensus-building over formal liberalization mandates [5].

In 1995, the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) marked a structural shift in global trade governance. Japan was among the founding members and actively supported its formation [20]. The country’s engagement in the WTO reaffirmed its commitment to multilateral liberalism. However, Japan also began to sense the limitations of multilateralism as the Doha Development Round faced early deadlocks [2]. Still, the 1990s saw no formal Japanese Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), reflecting both internal political economy constraints—such as resistance from the agricultural lobby—and a normative adherence to global multilateral rules [6].

Figure 1.

Japan’s trade policy evolution: from 1980

to 2025  Source: Compiled by the

authors based on data from METI (2002–2023), White Papers on International

Economy and Trade, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. URL: https://www.meti.go.jp/english/report/index.html

(Date of Access 11.07.2025).

Source: Compiled by the

authors based on data from METI (2002–2023), White Papers on International

Economy and Trade, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. URL: https://www.meti.go.jp/english/report/index.html

(Date of Access 11.07.2025).

According to the White Papers on International Economy and Trade published annually by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), Japan’s trade strategy throughout the 1980s and 1990s prioritized industrial policy coordination and the development of regional production networks in East and Southeast Asia [8]. These policies reinforced Japan’s role as a high-value manufacturing and technological hub in the Asia-Pacific, fostering trade complementarity with developing economies. However, they did not translate into legal commitments under bilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) or Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs), which Japan largely avoided during this period [6].

As illustrated in the trade policy timeline (Figure 1), this era is characterized by the absence of formal treaty activity, with the graph showing no significant inflection points in Japan’s FTA engagement before the early 2000s. The modest and linear growth of regional economic dialogue—primarily through mechanisms like APEC—reflects Japan’s commitment to soft multilateralism rather than binding liberalization frameworks [9]. The prevailing view within Japan’s economic bureaucracy emphasized the strategic use of ODA, export credit, and industrial cooperation as instruments of economic diplomacy rather than legal-institutional integration [4].

This historical phase thus portrays Japan as a “status quo power” in the global trade regime—one that leveraged the institutional architecture of GATT and, later, the WTO to maintain favorable export conditions without pushing for structural reform of the global trade order [20]. It was not until the early 21st century that this inertia was disrupted, as shifting regional dynamics and the rise of China forced Tokyo to recalibrate its approach to trade governance through more assertive bilateral and mega-regional frameworks.

2. Institutionalizing bilateralism: Japan’s tactical adaptation in regional trade (2000–2015)

The period from 2002 to 2015 marked Japan’s transition from multilateral reliance to a more assertive and diversified bilateral trade strategy, reflected in a rapid expansion of Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) [8,9]. These agreements were negotiated amid growing regional competition and trade liberalization trends in East and Southeast Asia, particularly in response to China’s increasing influence through mechanisms like the ASEAN+1 Free Trade Agreements and its broader trade diplomacy [12].

Table 1 outlines Japan’s principal EPAs concluded during this phase, beginning with the Japan–Singapore EPA in 2002—Japan’s first formal bilateral trade agreement. As a low-risk, services-oriented agreement, it served as a valuable learning platform for Japanese trade negotiators [16]. This was soon followed by the Japan–Mexico EPA (2005), a strategic move to expand Japan’s economic footprint into Latin America and mitigate over-dependence on East Asian markets. These early agreements prioritized tariff reductions on industrial goods while maintaining protective clauses for domestic agriculture, reflecting Japan’s internal political economy dynamics.

This bilateral momentum accelerated with the conclusion of EPAs with Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines, all of which reflected Japan’s dual ambition: to secure stable export markets and reinforce geopolitical ties in a rapidly integrating Asia-Pacific region. The Asia Economic Partnership Strategy released by METI in 2006 codified these objectives, aligning trade policy with broader diplomatic and industrial goals [8,9].

Table 1.

Comparative overview: Japan’s EPAs 2002–2015

|

Agreement

|

Year

in force

|

Level

of trade liberalization

|

Key

objectives

|

Japan’s

Strategic Achievements

|

|

Japan–Singapore

EPA

|

2002

|

Goods: 92.1% tariff

elimination; Services: GATS-style liberalization in finance, telecom,

legal, transport. The agreement excludes agriculture/fisheries.

|

First

EPA; focused on services, investment, minimal agricultural coverage

|

First

EPA; strategic entry into ASEAN; model for future FTAs.

|

|

Japan–Mexico

EPA

|

2005

|

Goods: ~98.4% liberalized

over time, but with agricultural exclusions and autos phased with quotas.

(Japan’s national automobile industry protection); Services: finance,

telecom, professional, construction.

|

Strengthen

trade and investment flows; facilitate industrial goods exchange.

|

Access

to Latin America, diversification beyond Asia.

|

|

Japan–Malaysia

EPA

|

2006

|

Goods: 97% liberalized

within 10 years;

Services: finance, education, health, tourism. Excludes

non-manufacturing FDI.

|

Expand

trade and economic cooperation: strong industrial focus.

|

Strengthened

access to Malaysian supply chains and to ASEAN

|

|

Japan–Indonesia

EPA

|

2007

|

Goods: 90% liberalized; Services:

construction, transport, legal, finance. Gradual liberalization in

agriculture/services.

|

Labor

mobility provisions; staged liberalization; trade ties.

|

Bilateral

cooperation on energy, infrastructure

|

|

Japan–Thailand

EPA

|

2007

|

Goods: ~95% trade

liberalized; Services: GATS-level access in several sectors. Most

agriculture excluded.

|

Investment

and IPR chapters; automobile sector liberalization

|

Reinforced

Japanese FDI in ASEAN. Preserved Japan’s auto sector lead in Thailand.

|

The bulk of the EPA activity during this period focused on ASEAN member states, reflecting Japan’s long-standing production networks and foreign direct investment (FDI) interests in Southeast Asia. EPAs with Malaysia (2006), Indonesia (2007), Thailand (2007), the Philippines (2008), and Vietnam (2009) offered varying degrees of tariff liberalization, typically excluding or limiting coverage of sensitive agricultural goods to accommodate domestic political economy constraints [9]. Notably, several agreements also included provisions for human capital mobility, particularly in the case of agreements with the Philippines and Indonesia, which allowed for the entry of nurses and caregivers—an exceptional feature in Japan’s generally restrictive immigration regime [6].

The ASEAN–Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership (AJCEP), signed in 2008, was designed to harmonize and supplement the pre-existing bilateral EPAs with ASEAN member states. As a plurilateral framework, it marked Japan’s initial experimentation with broader regional economic architecture and served as an institutional bridge toward more integrated regionalism [9]. AJCEP consolidated rules of origin, streamlined customs procedures, and introduced a limited services framework, though its depth remained modest by later standards [2].

Japan’s EPA network also extended westward, with agreements concluded with India (2011), Peru (2012), and Switzerland (2009). These deals reflected Tokyo’s desire to diversify economic partnerships beyond East Asia and secure access to critical raw materials, energy supplies, and new investment channels [13]. The Japan–India CEPA was particularly notable as a strategic hedge against China's increasing influence in South Asia, offering preferential access to India’s large consumer market and manufacturing base. Meanwhile, the Japan–Switzerland EPA helped to build institutional experience with European markets and laid the groundwork for subsequent negotiations with the European Union.

Despite their growing number and geographical diversity, most of these EPAs remained relatively narrow in rule-making depth. While they achieved significant progress in tariff reduction—particularly in industrial goods—they provided limited enforceability in emergent areas such as digital trade, competition policy, and investment-state dispute mechanisms [15]. Nonetheless, they played a foundational role in preparing Japan for deeper and more comprehensive trade regimes. These agreements enabled Japan to develop procedural expertise, legal frameworks, and negotiating capacity that would later underpin its leadership in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and participation in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) [3,16].

This phase of bilateralism thus served not only as a tool of economic diplomacy but also as a technical and strategic rehearsal for Japan’s broader engagement in multilateral trade governance.

3. Regional integration and the rise of mega-regional blocks (2015–2024)

In the aftermath of prolonged stagnation in WTO-centered multilateral negotiations and increasing geopolitical uncertainty, Japan adopted a more assertive role in shaping regional trade architecture through mega-regional agreements [20]. This strategic turn was catalyzed by two key events: the collapse of the Doha Development Round and the United States’ withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017 [16]. Confronted with these systemic disruptions, Japan emerged as a principal architect of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), assuming leadership in preserving high-standard trade rules among like-minded Asia-Pacific economies [3].

At the same time, Japan actively engaged in the ASEAN-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)—a more inclusive but less ambitious framework in terms of rulemaking, which nonetheless covers over 30% of global GDP and includes 15 countries [2]. These two agreements—complementary in geographic scope but contrasting in regulatory ambition—form the cornerstone of Japan’s 21st-century trade diplomacy. They reflect a pragmatic blend of liberal institutionalism and geopolitical hedging.

Table 2 summarizes Japan’s key Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) and regional frameworks during the mega-regional era. From the CPTPP’s legally binding commitments, strong digital trade chapters, and intellectual property protections to RCEP’s flexible rules-based inclusivity, Japan has calibrated its trade strategy to ensure both economic competitiveness and normative influence [17].

In parallel, Japan has deepened trade and economic ties with advanced industrial economies, including the European Union through the EU–Japan EPA (2019) and the United Kingdom through the UK–Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement [18]. These agreements reflect Tokyo’s ambition to position itself as a bridge between Asia and Europe, while also insulating its trade policy from geopolitical shocks such as Brexit (Cabinet Office, 2022). The upcoming revision of the ASEAN–Japan EPA, scheduled for post-2025, further underscores Tokyo’s intent to modernize legacy agreements by incorporating provisions on digital trade, green economy, and sustainable development [1].

Table 2.

Comparative overview: Japan’s EPAs (2015–2024)

|

Agreement

(Member countries) |

Year in force

|

Level of trade

liberalization

|

Key objectives

|

Japan’s Strategic

Achievements

|

|

CPTPP (Australia,

Canada, Mexico, Malaysia, Peru, Chile, New Zealand, Vietnam, Singapore,

Brunei)

|

2018

|

Goods: 99% liberalization; Services:

digital, financial, investment, transport. Excludes ~1% sensitive goods.

|

High standards on IP,

SOEs, e-commerce, labor

|

Leadership in

rulemaking, diversification from US/China

|

|

EU–Japan EPA (European

Union countries)

|

2019

|

Goods: 97% Japan, 99% EU

goods liberalized; Services: digital, finance, telecom, data flows. Agriculture

under quotas.

|

Mutual recognition of

standards, GI protection. Deepen EU-Asia trade ties.

|

Expanded market share

for autos and electronics. Deep integration with largest single market.

|

|

UK–Japan CEPA

|

2021

|

Same liberalization as

EU EPA; Agriculture under quotas.

|

Ensure post-Brexit

continuity and digital cooperation.

|

Secured first UK

post-Brexit deal, digital alignment

|

|

RCEP (ASEAN+5: China,

South Korea, Australia, New Zealand)

|

2022

|

Goods: ~92% liberalized; Services:

finance, telecom, e-commerce phased. Agriculture partly excluded.

|

Establish unified Asia

trade zone.

|

Strengthened supply

chains; economic presence with China/Korea.

|

|

Japan–Australia

Digital Trade Rules (Framework)

|

2022

|

Goods: Not applicable;

Services: liberalized digital, data flow, e-commerce.

|

Facilitates digital

economy cooperation, cross-border data flow

|

Norm-setting in

digital trade, regulatory alignment with trusted partners

|

|

Japan–Cambodia EPA

(bilateral upgrade to AJCEP)

|

2023

|

Under negotiation

|

Incorporates modern

provisions on services and investment

|

Deepens bilateral

ties, supports Cambodia’s industrialization

|

|

UK Accession to CPTPP

|

2023 (signed), 2025 (ratification)

|

95–99% of tariff lines

|

UK becomes first

non-Pacific entrant, commitment to high-standard rules

|

Expands CPTPP’s global

reach, Japan as gatekeeper of standards

|

|

Japan–Philippines EPA

Upgrade

|

2024–2025 (negotiation

phase)

|

In development

|

To include labor

mobility, digital trade, dispute mechanisms

|

Strengthens bilateral

labor frameworks and ASEAN cooperation

|

|

Japan–ASEAN EPA

(upgraded)

|

Ongoing negotiations

|

In development

|

Inclusion of digital

trade and services

|

Modernizing older

framework, ASEAN-centric approach

|

Each agreement represents a distinct modality within Japan’s broader strategic vision: the CPTPP and EU–Japan EPA position Japan as a rule-shaping middle power, while RCEP serves to stabilize supply chains and engage a broader set of regional partners. The UK–Japan CEPA exemplifies Japan’s ability to respond flexibly to shifting external conditions, and ongoing plurilateral efforts illustrate its evolving role in the architecture of global trade governance [12].

Japan’s transition to mega-regional trade frameworks was catalyzed by multiple systemic shocks, notably the collapse of the Doha Round of WTO negotiations and the United States’ withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in January 2017 [15]. In response to these setbacks in the multilateral system, Japan assumed a leadership role in reviving the TPP. Through sustained diplomatic engagement, Tokyo facilitated the agreement’s relaunch as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The CPTPP was signed in March 2018 and entered into force in December of the same year, with Japan completing domestic ratification in April 2019 [3].

The CPTPP includes 11 founding members: Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam. In July 2023, the United Kingdom became the first new acceding country, with formal entry pending ratification by all members. The CPTPP establishes high-standard trade disciplines, including legally binding commitments on e-commerce, intellectual property (IP), state-owned enterprises (SOEs), labor standards, and environmental protection [3].

Economically, the CPTPP provides Japan with preferential access to ten dynamic markets, supporting significant export growth in automobiles, precision machinery, and electronics. It also enhances Japan’s supply chain resilience, especially in light of global disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic and rising geopolitical tensions [13]. Domestically, CPTPP-related reforms contributed to Abenomics, driving liberalization in agriculture, services, and digital regulation [7].

On the global stage, the CPTPP functions as a WTO-plus platform, reinforcing liberal norms and offering an institutional alternative to China-led trade mechanisms. Japan’s leadership has positioned it as a norm entrepreneur in the Indo-Pacific, advocating for transparent, rules-based economic governance [17].

Concurrently, Japan was a key factor in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), an ASEAN-led initiative signed in November 2020. RCEP brings together 15 Asia-Pacific economies—the ten ASEAN nations, plus Australia, China, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand—and entered into force in January 2022 [2]. With a combined GDP of approximately US$25.9 trillion, RCEP accounts for nearly 30% of global trade, making it the largest free trade agreement in history by economic size [19].

Japan’s dual participation in both the CPTPP and RCEP embodies a pragmatic hedging strategy. While the CPTPP advances high-standard, legally enforceable norms, RCEP offers broader geographic inclusivity and political flexibility. Together, these agreements enable Japan to balance rule-making ambition with regional economic engagement, reinforcing its strategic posture as both a liberal power and a bridge-builder in the evolving Indo-Pacific order.

4. Trade and investment outcomes of Japan’s regional economic integration

Japan’s deepening participation in regional trade frameworks has yielded tangible economic dividends, particularly in terms of expanded trade volumes, diversification of export destinations, and growth in foreign direct investment (FDI) flows. By 2023, Japan had concluded 23 Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs), covering over 80% of its total trade volume, according to data from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry [15]. This extensive network has not only secured preferential market access for Japanese industries, but also contributed to the stabilization of supply chains through enforceable rules on investment protection, technical standards, and dispute resolution [11].

Empirical studies by the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) further confirm that EPAs have enabled Japanese firms—particularly in the automotive, electronic machinery, and pharmaceutical sectors—to penetrate non-traditional markets in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Europe. For example, Japanese exports to Mexico and Vietnam have more than doubled since the conclusion of respective EPAs, and bilateral investment with India surged following the Japan–India CEPA [4]. These patterns demonstrate that Japan’s regional trade strategy has both quantitative and qualitative dimensions, reshaping export structures and deepening economic interdependence across the Indo-Pacific.

The data presented in Table 3 offers a longitudinal perspective on the evolution of Japan’s EPA-driven trade policy from the early 2000s to projections for 2025. It reflects a steady increase in the volume of trade with EPA partners, and more importantly, a growing share of EPA countries in Japan’s overall trade portfolio. This shift not only indicates increased market penetration, but also a strategic reorientation of Japan’s external economic policy—from a reliance on traditional G7 markets to a broader, more diversified constellation of regional and transregional partners [6].

The growth of EPA-linked investment flows is also notable. Between 2010 and 2022, Japan’s outward FDI stock to EPA partner countries increased by over 40%, particularly in sectors like automotive production in ASEAN, renewables in Latin America, and digital services in Australia and the UK [1]. These flows are underpinned by EPA chapters on investment liberalization, investor protection, and dispute settlement, which create predictable environments for long-term strategic investment.

Table 3.

Japan’s trade and investment with EPA partners (2000–2025)

|

Year

|

Total

Trade Volume (¥ Trillion)

|

Share

of EPA Partners in Trade (%)

|

Japanese

Exports to EPA Countries (¥ Trillion)

|

FDI

Outflows to EPA Countries (¥ Trillion)

|

Top

EPA Destinations

|

|

2000

|

89.2

|

9.3

|

8.3

|

3.5

|

ASEAN

(esp. Thailand)

|

|

2005

|

110.5

|

16.7

|

18.5

|

5.4

|

ASEAN,

Mexico

|

|

2010

|

127.8

|

28.0

|

30.5

|

6.2

|

ASEAN,

India

|

|

2015

|

139.0

|

41.2

|

41.6

|

8.9

|

ASEAN,

Australia

|

|

2018

|

153.5

|

53.5

|

51.2

|

10.5

|

Vietnam,

Canada

|

|

2020

|

146.2

|

60.4

|

48.9

|

9.8

|

Vietnam,

EU

|

|

2022

|

165.0

|

72.1

|

59.6

|

12.7

|

EU,

Vietnam, UK

|

|

2025

(projected)

|

180.0

|

80.0

|

65.0

|

13.5

|

CPTPP+UK,

ASEAN

|

To assess the tangible outcomes of Japan’s regional economic integration strategy, it is essential to examine the evolution of its trade and investment flows with partner countries under EPA frameworks. The following indicators illustrate how Japan's economic engagements have deepened and diversified over the period from 2000 to 2025.

Expansion of EPA trade coverage

In 2000, EPA-covered partners accounted for merely 9.3% of Japan’s total trade, reflecting initial reliance on multilateral frameworks and hesitation toward binding bilateral agreements. By 2015—after EPAs with ASEAN, Latin America, and South Asia—the share rose to 41%, and it further increased to over 72% by 2022, with a projected 80% in 2025. This trend aligns with the entry into force of mega-regionals such as the CPTPP (2018) and RCEP (2022), which significantly expanded Japan’s trade engagement across the Indo-Pacific [2].

Export growth to EPA partners

Exports to EPA partners grew from ¥8.3 trillion in 2000 to nearly ¥60 trillion by 2022, marking an over sevenfold increase [5]. Notable growth was observed in machinery, automotive parts, and precision instruments, sectors that benefited from cumulative rules of origin, harmonized standards, and reduced non-tariff barriers [8]. Following CPTPP and the EU–Japan EPA implementation, exports to Vietnam, Canada, and the EU saw substantial increases—helping Japan offset stagnation in established markets like the United States and navigate trade tensions between the U.S. and China [20].

Rising FDI outflows and supply chain integration

Japan’s outward FDI to EPA countries more than tripled—from ¥3.5 trillion in 2000 to ¥12.7 trillion in 2022—suggesting that EPAs have reduced investment risks through political and regulatory frameworks [20]. ASEAN countries—particularly Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia—received the bulk of this investment, supporting manufacturing and infrastructure development. The CPTPP and RCEP further enabled Japanese firms to integrate into regional value chains, optimizing production through cost-sharing and labor allocation [2]. The projected ¥13.5 trillion in 2025 FDI reflects growing confidence in EPA-driven investment regimes, including in digital trade and green technologies, supported by recent UK digital trade protocols and DEPA initiatives [1,2].

Strategic diversification and shock absorption

This diversification reduced Japan’s overreliance on major economies like the U.S. and China, fostering a multipolar trade network. During crises—such as the COVID-19 pandemic and post-2022 supply chain disruptions—exports to CPTPP and ASEAN partners provided critical economic stability, while institutional cooperation within RCEP and the ASEAN + Japan framework helped absorb and mitigate shocks [3].

Policy implications

The data supports several conclusions relevant to trade policy:

· EPAs have served as effective tools for economic risk mitigation and regional engagement.

· Japan’s dual-track strategy—high-standard agreements (CPTPP, EU–Japan EPA) alongside inclusive, lower-bar frameworks (RCEP)—has enabled both normative leadership and geopolitical flexibility.

· Continued institutional innovation, particularly in digital and green trade, will be essential for sustaining these gains.

· Japan’s role as a "gatekeeper" of accession to CPTPP (e.g., UK, Taiwan, China) further institutionalizes its position as a normative power in global trade governance.

5. Strategic and economic implications for Japan: outlook toward 2030

These trade agreements offer Japan diversified export markets, institutional leverage in Asia, and opportunities to shape regional norms in digital and green trade [1,3]. They align with Japan’s broader Indo-Pacific strategy, particularly the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) vision, which emphasizes infrastructure, digital connectivity, and sustainable economic systems [10]. According to WTO data, Japan’s FTA coverage ratio reached 52.2% by 2023, reflecting its deepening engagement in bilateral and plurilateral trade regimes [20]. Furthermore, the Resilient Supply Chain Initiative, launched with India and Australia in 2021, supports Japan’s efforts to de-risk critical production dependencies [14].

Nevertheless, Japan continues to face domestic opposition from agricultural lobbies, which challenge liberalization under EPAs, and must navigate the delicate balance between implementing high-standard trade rules and ensuring domestic inclusivity.

Looking ahead, Japan is positioned to play a critical role in expanding CPTPP membership (with accession applications from the UK, Taiwan, and China), advancing digital trade governance, and fostering sustainable economic integration [17]. To consolidate these gains, policymakers should prioritize reinforcing dispute settlement mechanisms, aligning carbon border adjustment systems, and strengthening cooperation with Global South partners, particularly in areas of climate resilience and digital infrastructure [6]. Japan’s role as a bridge-builder between Western liberal norms and Asian pragmatism will be vital as the global economy confronts decarbonization imperatives, digital fragmentation, and multipolar governance structures.

Conclusion

Japan’s trade diplomacy between the 1980s and 2025 demonstrates a profound and adaptive transformation—from reliance on multilateralism through GATT/WTO mechanisms, to experimental bilateralism, and finally to strategic leadership in rule-making mega-regional trade frameworks. This recalibration was not a linear progression but rather a series of calculated responses to both endogenous economic pressures and exogenous systemic disruptions—ranging from the stagnation of the Doha Round to the geopolitical vacuum left by the U.S. withdrawal from the TPP.

Through the construction and leadership of the CPTPP and active participation in the RCEP, Japan has redefined its role from a passive norm-taker to an assertive norm entrepreneur in the Indo-Pacific. These agreements, differing in ambition and regulatory depth, reflect a dual-track strategy: CPTPP embodies Japan’s liberal, high-standard vision of economic governance, while RCEP serves as a pragmatic vehicle for inclusive regionalism and supply chain anchoring.

Importantly, Japan’s trade policy has become a tool of economic statecraft, supporting broader objectives such as supply chain diversification, domestic reform leverage, and geopolitical balancing—especially vis-à-vis China’s assertive trade initiatives. The economic outcomes have been significant: Japanese exports have diversified geographically; investor confidence has been bolstered through rules-based disciplines; and domestic sectors, including agriculture and digital services, have begun to modernize under the pressure and promise of international obligations.

Looking forward, the durability of Japan’s leadership in regional trade governance will depend on its capacity to maintain cohesion among CPTPP members, ensure compliance with high-standard disciplines, and shape accession processes without diluting core principles. As new applicants—including China, Taiwan, and the Philippines—seek entry into CPTPP, Japan’s stewardship will be tested on the frontlines of geoeconomic competition and institutional legitimacy.

In conclusion, Japan’s trajectory affirms that trade policy, when aligned with strategic foresight and normative clarity, can serve as a stabilizing force in a fragmented world economy—an indispensable lesson for both scholars and policymakers navigating the uncertainties of 21st-century global trade.

Источники:

2. Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2022) The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement: A New Paradigm in Asian Cooperation. Policy Brief. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/792516/rcep-agreement-new-paradigm-asian-cooperation.pdf (дата обращения: 10.07.2025).

3. Hillman J., Goodman M. P. (2020) Digital Trade and the CPTPP: A High‑Standard Template. Center for Strategic and International Studies. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.csis.org/analysis/digital-trade-and-cptpp-high-standard-template (дата обращения: 10.07.2025).

4. JETRO. (2021) Utilization of EPAs and FTAs by Japanese Companies. Survey Report. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.jetro.go.jp/en/reports/survey/pdf/epa_utilization.pdf (дата обращения: 14.07.2025).

5. JETRO. (2022) Global Trade and Investment Report. Japan External Trade Organization. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.jetro.go.jp/en/reports/statistics.html (дата обращения: 14.07.2025).

6. Kawase T., Oba M., Inomata S., Toyoda M. (2024) Challenges for Japan’s Trade Policy: Rebuilding a Rules-Based International Order & Resilient Supply Chains with the Global South. Rieti. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/papers/contribution/kawase/14.html (дата обращения: 14.07.2025).

7. Matsumura K. (2021) CPTPP and Japan’s Agricultural Reform Trajectory. Policy Research Institute, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.osipp.osaka-u.ac.jp/archives/DP/2014/DP2014E003.pdf (дата обращения: 14.07.2025).

8. METI. (2002–2023) White Papers on International Economy and Trade. Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.meti.go.jp/english/report/index.html (дата обращения: 14.07.2025).

9. MOFA. (2023) List of EPAs and FTAs. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/fta/index.html (дата обращения: 14.07.2025).

10. MOFA-Japan. (2021) Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) Vision. Policy Outline. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.mofa.go.jp/fp/page1e_000084.html (дата обращения: 14.07.2025).

11. National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR). (2023). Japan’s Role and Strategy in the Formation of Digital Trade Rules in the Indo-Pacific.

12. Oba M. (2022) Japan and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). ERIA Discussion Paper No. 461. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.eria.org/uploads/media/discussion-papers/FY22/Japan-and-the-Regional-Comprehensive-Economic-Partnership-%28RCEP%29.pdf (дата обращения: 10.07.2025).

13. OECD. (2023) Trade Policy Review: Japan. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.oecd.org/trade/trade-policy-reviews/ (дата обращения: 10.07.2025).

14. Prime Minister of Japan. (2021) Resilient Supply Chain Initiative Launch Statement. Official Government Statement. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/101_kishida/statement/2021/0628statement.html (дата обращения: 10.07.2025).

15. RIETI. (2024) EPA Impacts on Trade Structure and Industrial Competitiveness. Research Institute of Economy. Trade and Industry. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/publications/ (дата обращения: 10.07.2025).

16. Solís M. (2017) The Case for Leadership: Japan in the CPTPP. Brookings Institution. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-trans-pacific-partnership-the-politics-of-openness-and-leadership-in-the-asia-pacific/ (дата обращения: 10.07.2025).

17. Solis M., Katada S. N. // Asia‑Pacific Review. – 2022. – № 29(1). – p. 5–25. – url: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26572839.

18. UK Government (2023) Digital Trade Agreements: UK-Japan DEPA. Department for International Trade. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/digital-economy-partnership-agreement-depa (дата обращения: 17.07.2025).

19. UNCTAD. (2023) World Investment Report 2023: Investment in Sustainable Energy for All. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://unctad.org/webflyer/world-investment-report-2023 (дата обращения: 17.07.2025).

20. WTO (2024) Regional Trade Agreements Information System. World Trade Organization. [Электронный ресурс]. URL: https://rtais.wto.org (дата обращения: 17.07.2025).

Страница обновлена: 16.02.2026 в 16:53:29

Download PDF | Downloads: 14

Стратегический подход японии к региональной экономической интеграции: от двусторонних соглашений к мегарегиональным структурам

Nazarova D.V., Andronova I.V.Journal paper

Journal of International Economic Affairs

Volume 15, Number 3 (July-september 2025)

Abstract:

За последние два десятилетия торговая политика в отношении региональной экономической интеграции Японии претерпела глубокие структурные изменения. Первоначально приверженная либерализации торговли в рамках ГАТТ и ВТО и руководствовавшаяся осторожной экономической дипломатией, Япония в начале 2000-х годов перешла к двусторонним отношениям, прежде чем стать главным архитектором мегарегиональных торговых группировок, таких как Всеобъемлющее и прогрессивное соглашение о Транстихоокеанском партнерстве (CPTPP) и Региональное всеобъемлющее экономическое партнерство (RCEP). В этой статье рассматриваются стратегические причины, стоящие за этим переходом, освещаются институциональные изменения в торговой политике Японии, геополитические амбиции и меняющиеся приоритеты в Индо-Тихоокеанском регионе. Опираясь на официальные правительственные публикации, базы данных по международной торговле и экспертный анализ, авторы утверждают, что торговая политика Японии отражает сочетание стремления к нормотворчеству и расширения влияния посредством участия в региональной экономической интеграции в условиях фрагментации мирового порядка.

Keywords: Япония, двустороннее торговое соглашение, многостороннее торговое соглашение, региональная экономическая интеграция, торговая политика

JEL-classification: F02, F14, F15

References:

Aizawa T. (2022) Japan’s Digital Trade Strategy in the Indo-PacificNBR Analysis. Retrieved July 10, 2025, from https://www.nbr.org/publication/japans-digital-trade-strategy/

Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2022) The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement: A New Paradigm in Asian CooperationPolicy Brief. Retrieved July 10, 2025, from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/792516/rcep-agreement-new-paradigm-asian-cooperation.pdf

Hillman J., Goodman M. P. (2020) Digital Trade and the CPTPP: A High‑Standard TemplateCenter for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved July 10, 2025, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/digital-trade-and-cptpp-high-standard-template

JETRO. (2021) Utilization of EPAs and FTAs by Japanese CompaniesSurvey Report. Retrieved July 14, 2025, from https://www.jetro.go.jp/en/reports/survey/pdf/epa_utilization.pdf

JETRO. (2022) Global Trade and Investment ReportJapan External Trade Organization. Retrieved July 14, 2025, from https://www.jetro.go.jp/en/reports/statistics.html

Kawase T., Oba M., Inomata S., Toyoda M. (2024) Challenges for Japan’s Trade Policy: Rebuilding a Rules-Based International Order & Resilient Supply Chains with the Global SouthRieti. Retrieved July 14, 2025, from https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/papers/contribution/kawase/14.html

METI. (2002–2023) White Papers on International Economy and TradeMinistry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Retrieved July 14, 2025, from https://www.meti.go.jp/english/report/index.html

MOFA-Japan. (2021) Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) VisionPolicy Outline. Retrieved July 14, 2025, from https://www.mofa.go.jp/fp/page1e_000084.html

MOFA. (2023) List of EPAs and FTAsMinistry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved July 14, 2025, from https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/fta/index.html

Matsumura K. (2021) CPTPP and Japan’s Agricultural Reform TrajectoryPolicy Research Institute, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Retrieved July 14, 2025, from https://www.osipp.osaka-u.ac.jp/archives/DP/2014/DP2014E003.pdf

National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR). (2023). Japan’s Role and Strategy in the Formation of Digital Trade Rules in the Indo-Pacific.

OECD. (2023) Trade Policy Review: JapanOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved July 10, 2025, from https://www.oecd.org/trade/trade-policy-reviews/

Oba M. (2022) Japan and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)ERIA Discussion Paper No. 461. Retrieved July 10, 2025, from https://www.eria.org/uploads/media/discussion-papers/FY22/Japan-and-the-Regional-Comprehensive-Economic-Partnership-%28RCEP%29.pdf

Prime Minister of Japan. (2021) Resilient Supply Chain Initiative Launch StatementOfficial Government Statement. Retrieved July 10, 2025, from https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/101_kishida/statement/2021/0628statement.html

RIETI. (2024) EPA Impacts on Trade Structure and Industrial Competitiveness. Research Institute of EconomyTrade and Industry. Retrieved July 10, 2025, from https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/publications/

Solis M., Katada S. N. (2022). The Making of Economic Rule‑Makers: Japan’s Strategic Use of Mega‑FTAs Asia‑Pacific Review. (29(1)). 5–25.

Solís M. (2017) The Case for Leadership: Japan in the CPTPPBrookings Institution. Retrieved July 10, 2025, from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-trans-pacific-partnership-the-politics-of-openness-and-leadership-in-the-asia-pacific/

UK Government (2023) Digital Trade Agreements: UK-Japan DEPADepartment for International Trade. Retrieved July 17, 2025, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/digital-economy-partnership-agreement-depa

UNCTAD. (2023) World Investment Report 2023: Investment in Sustainable Energy for AllUnited Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Retrieved July 17, 2025, from https://unctad.org/webflyer/world-investment-report-2023

WTO (2024) Regional Trade Agreements Information SystemWorld Trade Organization. Retrieved July 17, 2025, from https://rtais.wto.org